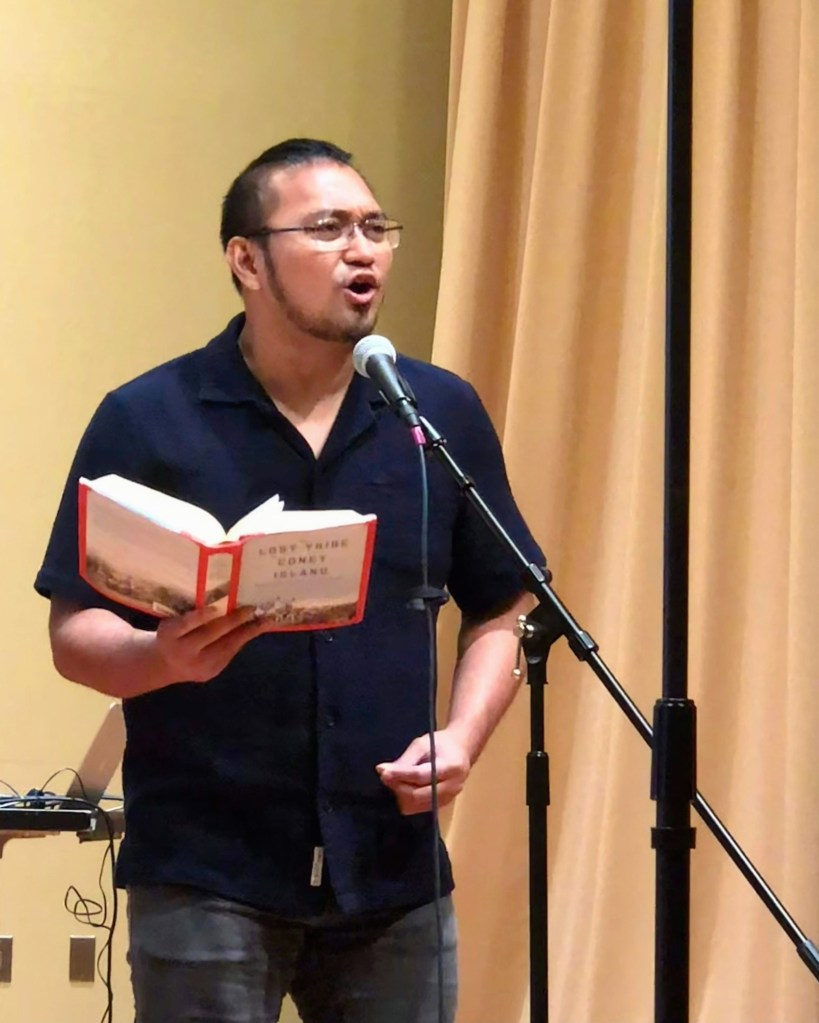

I stood up and faced the audience. The four physical books I brought at the sidelines now weighed heavily on me. My face couldn’t figure out whether it should give onlookers a scowl or a cold, hard stare. Clutching a book on one hand, I read aloud on the mic. I dramatized the texts I saw on the pages. Four times, I did this. Each time I did, I got a little more nervous than the last.

Onstage, I was F. Sionil Jose’s unnamed son of a Filipino plantation landlord in Rosales who grappled with the social ills that he is complicit to — all told in the novel Tree (1978). I was Claire Prentice in The Lost Tribe of Coney Island (2014), reporting the American imaginations of exoticized Igorots who were “displayed” at Coney Island’s human zoos in the early 1900s. I was Jose Antonio Vargas when his memoir Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen (2018) narrated his emotional turmoil of being found out as undocumented during the highest point in his journalism career. I was Sandra Nicole Roldan’s child protagonist in At the School Gate (2018) — she, who saw her world in Martial Law-laden Philippines of the 1970s while contending with her dissenting father’s unjust incarceration.

I wore my old Filipino accent in some readings. My English sounded different back in 2013. But since moving to Canada, each passing year in North America always felt like an opportunity to shed it off. It’s like wearing a Halloween costume to make white spaces accept you — “Ah, you’re one of us” — and avoid unconscious, yet lingering prejudices that come with being Othered. I chose to reclaim back that accent this time. Someone on social media criticized me for doing this once: “I feel offended, you’re making fun of ‘our’ accent.” Yung accent namin. “Namin” in the possessive, meaning “our.” The implication here was loud enough. He saw me, someone who was born and raised in the homeland, no longer belonging to that “our.” I had to clarify: No no, I’m not. The context is deeper. I used to sound like that. My need to reclaim it back IS the main story here.

The live world premiere of Liham unfolded in this manner in 2024 at New York’s MISE-EN Festival. Our team — mezzo-soprano Renee Fajardo (who also commissioned the work), pianist Vivian Kwok, and I — worked to make the work breathe for the first time onstage. As a song cycle comprising four art songs, I also decided to match each song with a live stage reading of texts. It was a difficult grind for me during our preparations, getting hefty work done in Montreal and Vancouver in a matter of days before pinning down our first rehearsals at Edmonton a month before the premiere. It was a consolation to see fellow composer and friend Sidney Boquiren attend the performance. After everything was said and done, we knew that this was only our test run in preparation for a bigger presentation.

==

With support from Vancouver-based Sound The Alarm: Music/Theatre, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts, we finally launch Liham: A Digital Song Cycle tomorrow on 12 June 2025, 12:00am PST (Vancouver time). Instead of a conventional digital/streaming music release, Liham (translation: “letter/mail”) comes in the form of a website platform: <lihamproject.com>. This multimedia iteration of the work features performances of four art songs by Renee Fajardo (also now Executive Producer), Vivian Kwok, and baritone Danlie Acebuque (fresh from his residency at the Vancouver Opera). Composed from a libretto by Revan Badingham III, the song cycle is recorded by Darren Wen at the University of British Columbia and later filmed in different locations with direction by Solara Thanh-Bình Đặng, cinematography by Rachel Chen, editing by Josh Aries, and colour grading by João Homem. We see the work unfold and reside within a website, designed by Joey Laguio.

As a memoir and a resonant love letter to the Filipinx spirit, Liham: A Digital Song Cycle offers a poignant reflection on numerous layers of Filipino Canadian identity, migration, and community. A June 12th release is no coincidence: it is the Philippines’ Independence Day and also a day within the month-long celebration of Filipino Heritage Month in Canada. To mark these occasions, this digital version of Liham features stories of four Filipino Canadians with various perspectives and life experiences: two business owners in British Columbia, Bennet Miemban-Ganata and Nigel Elivera; Vancouver-based visual artist Bert Monterona; and Toronto-based actor, playwright, and singer/songwriter Carolyn Fe. (Plato Filipino Restaurant and Pro-Tech Auto Repair — businesses owned by Miemban-Ganata and Elivera — served as filming locations for some art songs). Running true to the spirit of Liham, their stories come in the form of letters addressed to visitors. This is where song and story collide through a prism, revealing streaks of hidden colours that one ray of light embodies within.

“It was important to us to work with folks within our community here, and I wanted the project to tell their—our—stories, wherever that took us,” Fajardo shares. “This is a love letter to those of us who, for one reason or another, know what it’s like to have a heart constantly between identities, between oceans.” With contemporary classical music, storytelling, poetry, and film, we challenge prevailing narratives by affirming the validity of diverse Filipino experiences—whether born in Canada, newly arrived, or long-settled—without reducing them to stereotypes or trauma.

You can tell that I’m also wearing my writer hat behind the scenes. Coming from my four-week MacDowell artist residency in New Hampshire, I visited Vancouver to interview Miemban-Ganata, Elivera, and Monterona alongside Fajardo. (It is coincidental that I arrived ten days after the Lapu Lapu Day Festival tragedy — something that Liham also acknowledges). Following an interview with Carolyn Fe in Toronto, I got down on all fours to transcribe all interviews and present them in the way you will see in this new website.

I also updated an essay I wrote (“Notes on Liham”) that will serve as liner notes for the work’s release. This is a piece I previously wrote as program notes for last year’s world premiere.

You can read more and listen/watch the filmed version of Liham on June 12 (12am PST): <lihamproject.com>. I definitely urge you to read “Notes from the composer” at the end to get a broader picture behind the work’s creation.

Alongside this release, I will also produce a series of writings to accompany Liham: A Digital Song Cycle here on my website blog at <jurokimfeliz.com>.

Each essay will dabble on each art song of the Liham song cycle in sequence as I elucidate and reflect on musical details, some excerpts of the score, the attached stories and interviews, and other aspects I’ve seen as the composer of the work. I will post one essay every weekend starting on 28 June 2025, producing four essays in total within four weeks. This creates a space for interested folks to get a glimpse behind the universe that is Liham.

This project took five years to arrive at this point. The sheer time scale is quite astounding. As we now reach a culmination of all the work done, I hope that this creates and holds space for recognition of historically underrepresented folks amid a world that leaves systemic barriers, structures, and invisibilities largely unchecked.

Liham: A Digital Song Cycle is out on June 12, 12:00am PST: <lihamproject.com>.

This project is supported by Sound The Alarm: Music/Theatre, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts.