Putting such a title to this rather hefty update feels appropriate. As much as a huge surge of productivity washed over the past months, the next three months will leave me in a financial lull. The amount of investment we artists put in our work and practice can sometimes be unreasonable or nonsensical, but we always hope for the best. After all, some of the great things that happened so far have been the fruit of years of activity — sometimes even with work idling in the shelf for a long time! (After all, I did silently initiate an unofficial hiatus out of frustration sometime ago).

The ebb and flow of opportunities do not come consistently many times. I have to admit that I’m still the composer who hounds for calls for scores all over the place instead of building a more reliable creative network hub. For us coming from the developing world like the Philippines, the former has been the composer’s “normal route” due to the lack of access from greater collaborations among richer countries and their sprawling (but many times self-serving and self-contained) networks. I have to take note of this “self-contained” nature of artistic collaboration among white-dominated, dollar-infused economies. As a once younger composer in the Philippines who only got crumbs of this big pie (without getting a full glimpse of it), I now find it quite appalling. You see younger composers nowadays from the Global North being celebrated, while the rest are deliberately unseen. Hence, I continue speaking about North America’s inclusion and diversity within the arts as “blind” and “bordered” — the blindness is heavily implicated in the fact that the concept of nation-states like Canada, the United States, etc., enact borders to protect resources, tax bases, consolidations of power. There lies the “insiders” versus the “outsiders.”

But the rhythms have kept the momentum going. I have so many things to talk about that I have to split this in two parts! Here are some drops of activity that rippled within reach:

- Upcoming world premiere of Kinaligta-án at St. George by the Grange (Toronto)

It was my first time to write for harpsichord. Seemingly out of nowhere, Wesley commissioned me a work back in 2021 at a time when I was struggling to grapple with my own invisibility as a composer. (It also didn’t help that I decided to enforce a hiatus out of extreme frustration and focus on Grumpy Kitty Boy instead during the pandemic). I saw this as an opportunity to reflect on things long forgotten: my fraying connections to the homeland, the harpsichord and the lute as once-forgotten instruments (Wesley’s harpsichord has a lute stop!), my memories of past lives that now lie dead after my move to Canada in late 2013, disintegrating pieces of hope in pushing a career as a composer. Memories of kundiman art song I used to play with classical singers popped up, and I just had to include Nasaan Ka Irog? (Nicanor Abelardo; title translates to “Where Are You, My Beloved?”) to further insinuate this inquiry.

The notes and time dilation within Kinaligta-án (trans. “things [deliberately?] long forgotten/bypassed”) came out while I had Mario Maker gameplays on YouTube running in the background. It’s a funny way to work. It did not influence the way I wrote the music, but juxtaposing such with circumstances of dealing with lockdown isolations and detachments from people I once knew makes my memory of the piece a little unhinged. I love the ambiguity of the title itself! It implies possibilities bordering on conspiracy (whether the act of forgetting is intentional or not), in which the trolling community in the Mario Maker video game does with their level creations to make fun of their fellow players.

Attend this all-harpsichord, all-contemporary music concert with Wesley Shen’s world premiere of Kinaligta-án on June 29th! Concert details are found HERE. The creation of this 14-minute work is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts.

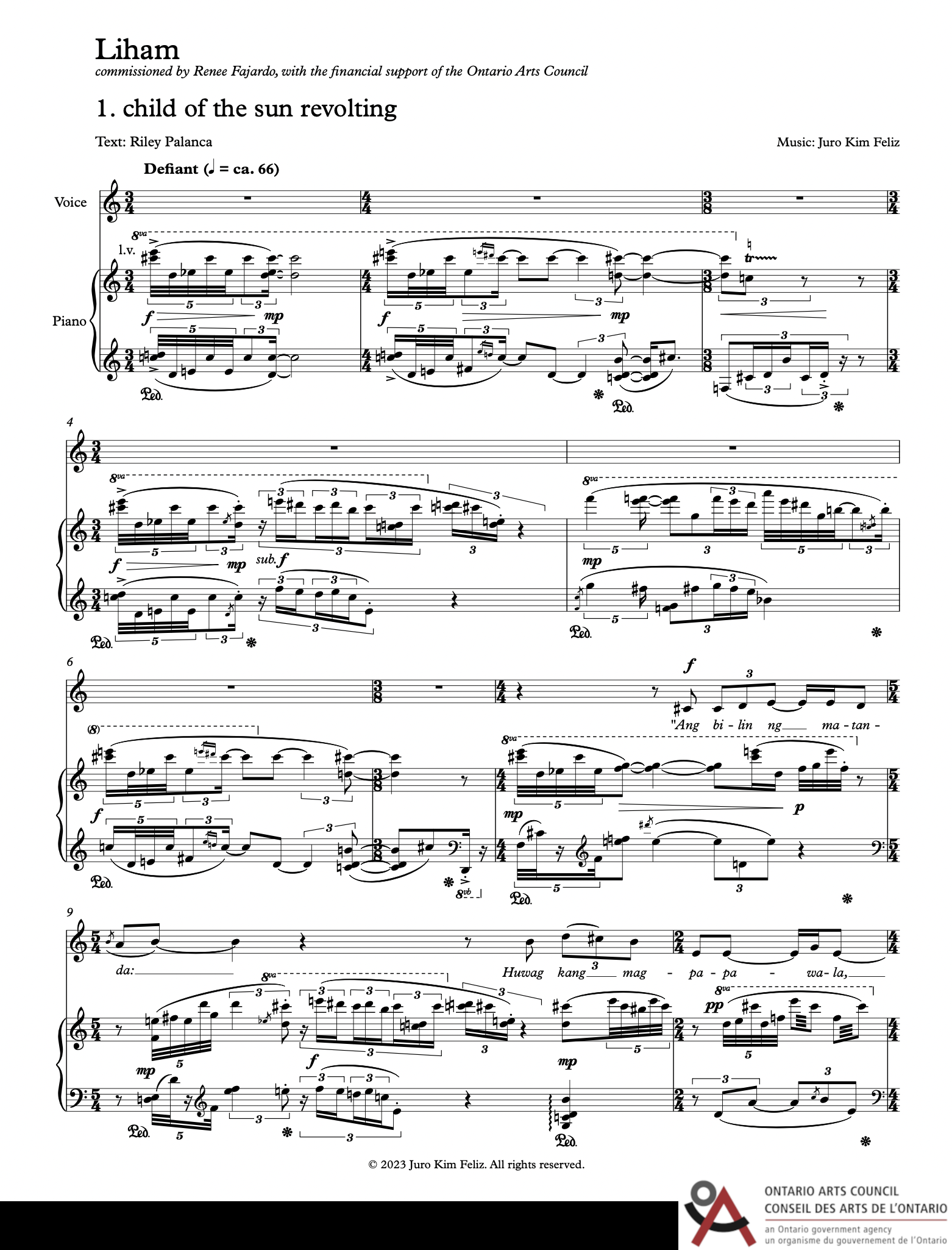

- New song cycle Liham supported by the Ontario Arts Council

I have lots to say about this project! After more than a year of doodling, failing, and experimenting with certain ideas, I finally laid down the double bar line of this song cycle last April. With four art songs for low voice and piano to boot, this project is so close to my heart that I now have a personal love-hate relationship with it.

Filipino mezzo-soprano Renee Fajardo commissioned this project in late 2021. Liham translates into “letter/mail,” in which she conceived the whole song cycle as a love letter to the Filipino creative spirit both within the homeland and the diaspora. Initially failing to contract a Filipino-Canadian writer to work on a libretto, I suggested playwright Riley Palanca to do it instead — Riley has been a long-time strong collaborator of mine for the past seven years since we first met in Montreal. They agreed to do the work, and the project set sail with a pilot art song. Both Tagalog and English texts came out in no time.

I initially wanted to take off from Claude Debussy’s Cinq Poèmes de Baudelaire to reimagine the Filipino kundiman art song. I wanted a dreamy sound with hints of antithetical romantic pandering, similar to how Debussy first emulated Wagner and have shunned it later. Musical quotation was in order, a nod to both Luciano Berio and Charles Ives whose second piano sonata Concord Sonata I love dearly. However, Riley’s text for the first art song (children of the sun revolting) was a shocker: the poem was a declaration of strong, revolutionary convictions! I loved it in every way, anyway. I decided that if I needed an antithesis to my whole compositional practice, it has to be about emulating classical music’s romanticism in the likes of Schumann or Verdi. It was decided then — this will be an opportunity to negate myself and imagine how I could do it.

It was not an easy process. Even after receiving arts funding from the Ontario Arts Council at the end of 2021, the journey was a very conflicting one since ideas were initially rubbing on me the wrong way. I decided that both the third and fourth songs should have hints of singer-songwriter elements like I would do Grumpy Kitty Boy: I deliberately wrote sections where the pianist has to do pop ballad improvisation with chords (written on the score) instead of actual notes. “Theatrical notes” written in the piano score (i.e. like a rose on a glass globe, or a random tune heard on the radio, or a chorus of church bells) run in counterpoint with the music without dictating it — my alternate ways of conceiving spatialization led me to embed poetics in the work, an underlying dramaturgy without being intrusive about it.

Musical quotation was also in full force for every song, but most especially in the second song: quoting actual kundiman melodies on the piano everywhere led me to ask many times, “Why am I doing all this?” Bits of pieces of songs lie scattered. Bituing Marikit. Mutya ng Pasig. Pakiusap. Bayan Ko. Anak Dalita. All of them attempt a dialogue with the singer’s mostly tonal melodies, those detached from all of their presences, awkwardness, and even brashness. My work on Kinaligta-án (that I previously wrote about) comes into mind here.

This is the “Filipino” of the diasporas, I thought. Fragmented. Scattered. Patched up. Some pieces of themselves are thriving, while some are buried and tucked inside. Some are probably even forgotten. The gaping hole bored through our homeland selves was transplanted in other lands, the great move not filling the void at all.

Plans for the digital world premiere of Liham with Fajardo and baritone Danlie Acebuque (with support from the Canada Council for the Arts) are currently underway. Watch out for it!

- American premiere of Ni ici, ni là-bas at Tempus Projects (Tampa, FL)

My work was selected for the music festival CAMPGround23 at Tampa, Florida last March. Their programming eventually nailed down my alto flute piece Ni ici, ni là-bas (Neither Here Nor There) for the concert program at Tempus Projects, a thriving creative hub smack in the middle of the increasingly gentrifying Ybor City. I noted that this performance will be the American premiere of the work.

Working with Julianna Eidle was fantastic! We eventually learned that all performances for this event will happen on the stairway of Tempus Projects, culminating into a theatre-dance installation in the main gallery. It was like ascending Fux’s Mount Parnassus, and I now remember this unorthodox setting whenever I see nice stairways in public buildings: “The alto flute piece could be performed here too!”

The American premiere of Ni ici, ni là-bas was made possible with the support of the SOCAN Foundation through a travel grant.

- World premiere of Kina-i-ngátan at Paradise Theatre (Toronto)

“Why is it not working properly?” We were testing my 6.1 surround setup with the Dante network at Paradise Theatre, and the connection is somewhat unreliable on my end. A friend would tell me months later, “It must be the dongle you’re using.” In any case, the time I requested to specifically test the audio in the venue was worth having, as all electronic setups should always require. Throughout the testing period, Goombine’s musings on cultural identity and ownership filled the space while textures of noisy electronic sounds rolled over from speaker to speaker (or as they should).

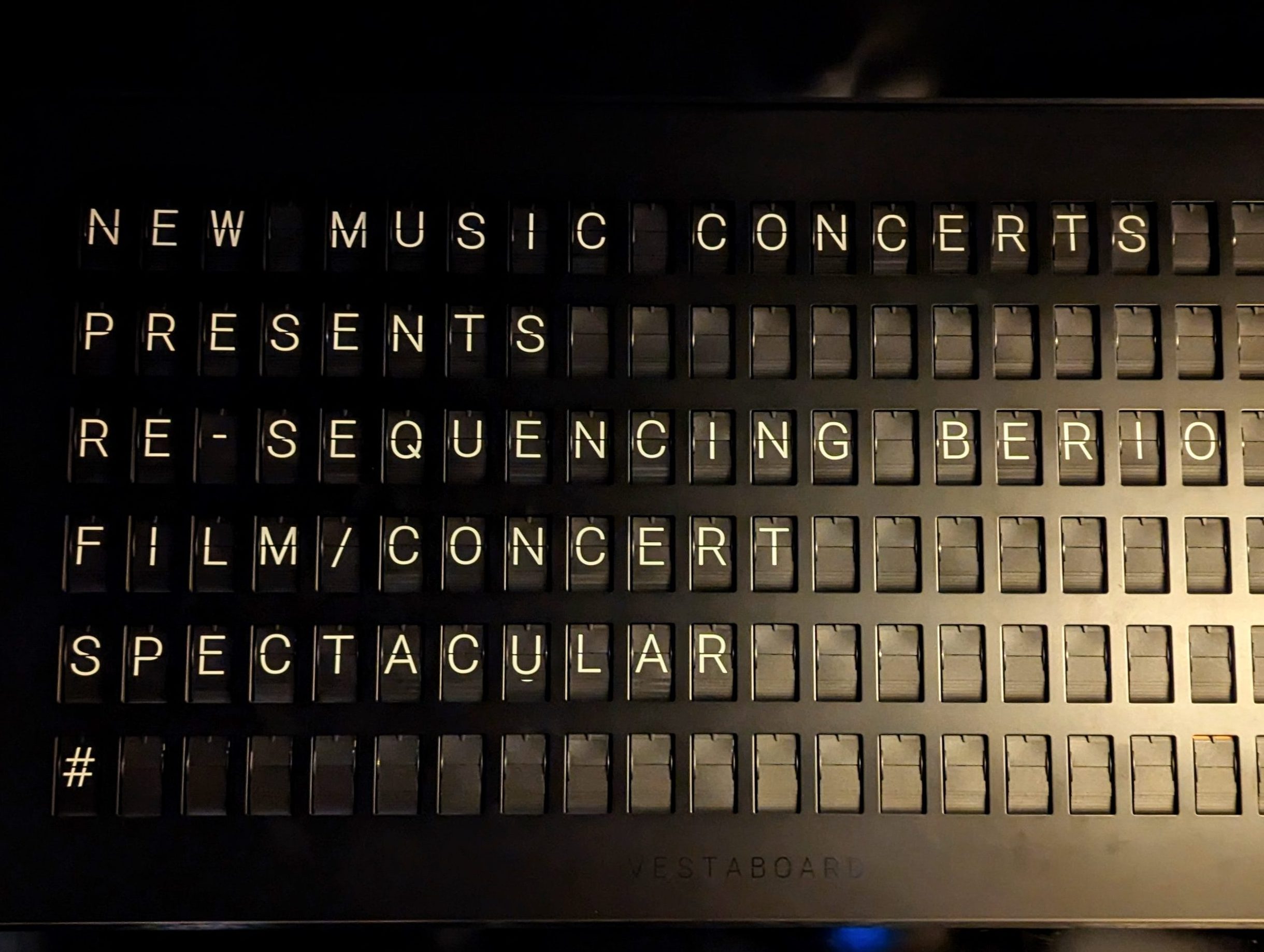

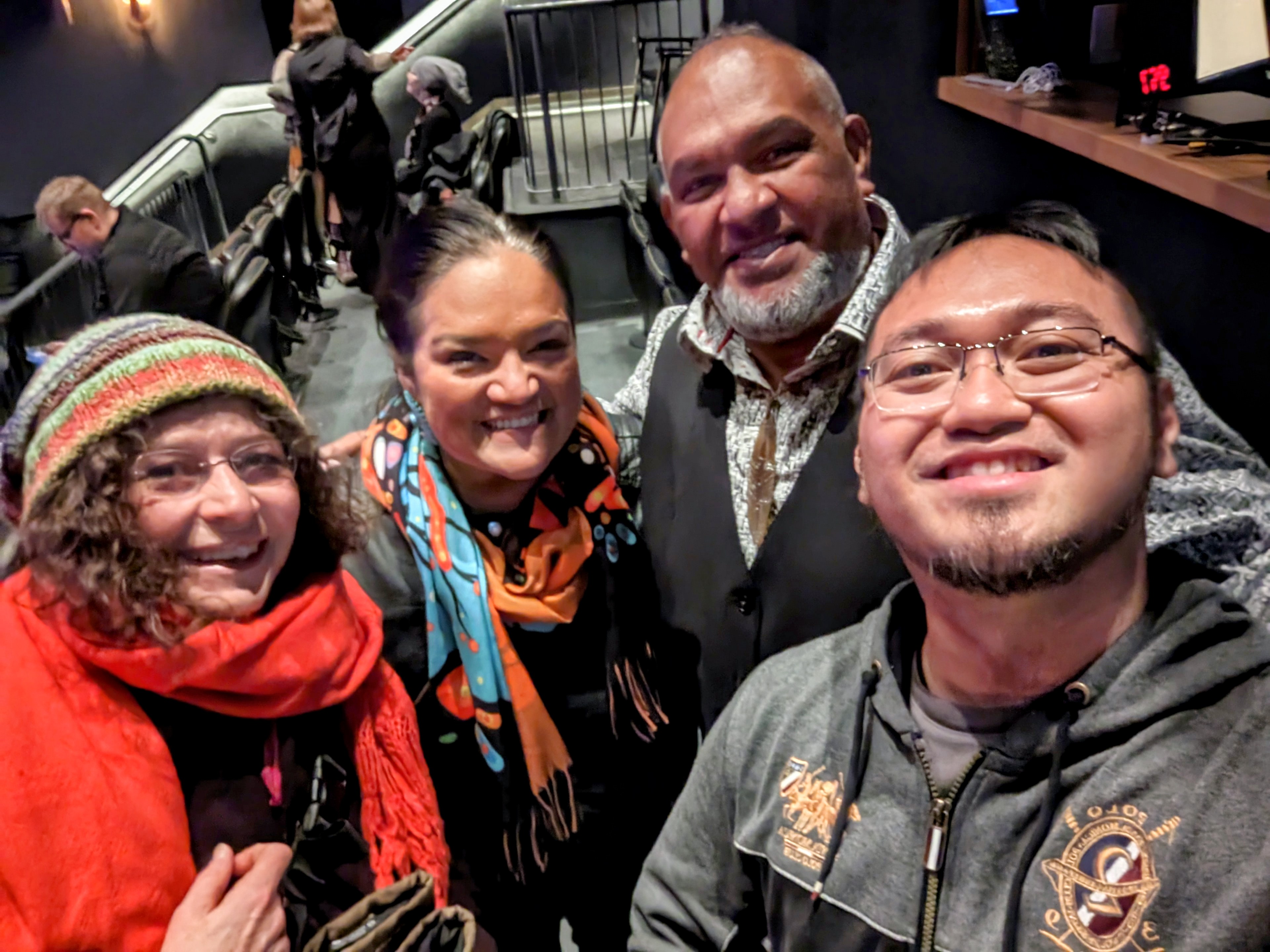

Presented by New Music Concerts, the next day’s world premiere was more than that. Trumpet virtuoso Guy Few finally punctuated trumpet music into the audio essay that now comprises the work Kina-i-ngátan. It can exist either as solo trumpet music, as an audio essay, or both fused together. Eventually receiving support from the Canada Council for the Arts, it was a project that took a year to finish! I was testing ideas on spatialization beyond using physical space as a musical medium. It all started with a Musicworks article that reported on cultural repatriation activities happening among Canada’s music venues — I already wrote an update about the whole project HERE. Aboriginal lore man Goombine (Richard Scott-Moore) was right at centre stage. I asked him during my interview to record his thoughts and use it for a future audio essay project, to which he wholeheartedly gave me permission. To sum it up, I found an opportunity to lay down the space for my journalism and composition ventures to interact and negotiate with each other as two separate entities. (Whether this runs in opposition to the notion of synthesis or not is perhaps subject to a bigger conversation). This is the spatialization that I find more significant beyond a mere fetishization of sound in physical space.

The most touching part of this world premiere is the fact that both Goombine (along with his wife Candace Scott-Moore) and Tranzac board member Brenna MacCrimmon graciously accepted my invitation to attend the concert. It was a reunion for all of us who found kinship and family through the repatriation of once-lost objects in April 2022. (It still gives me the fuzzies as I write about it). Even after the technical difficulties of mounting this project, we now arrive at a place beyond journalism or composition or professional work altogether — every one of us understood what really mattered, and we continued upholding value to it. The title Kina-i-ngátan affirms this prized moment.

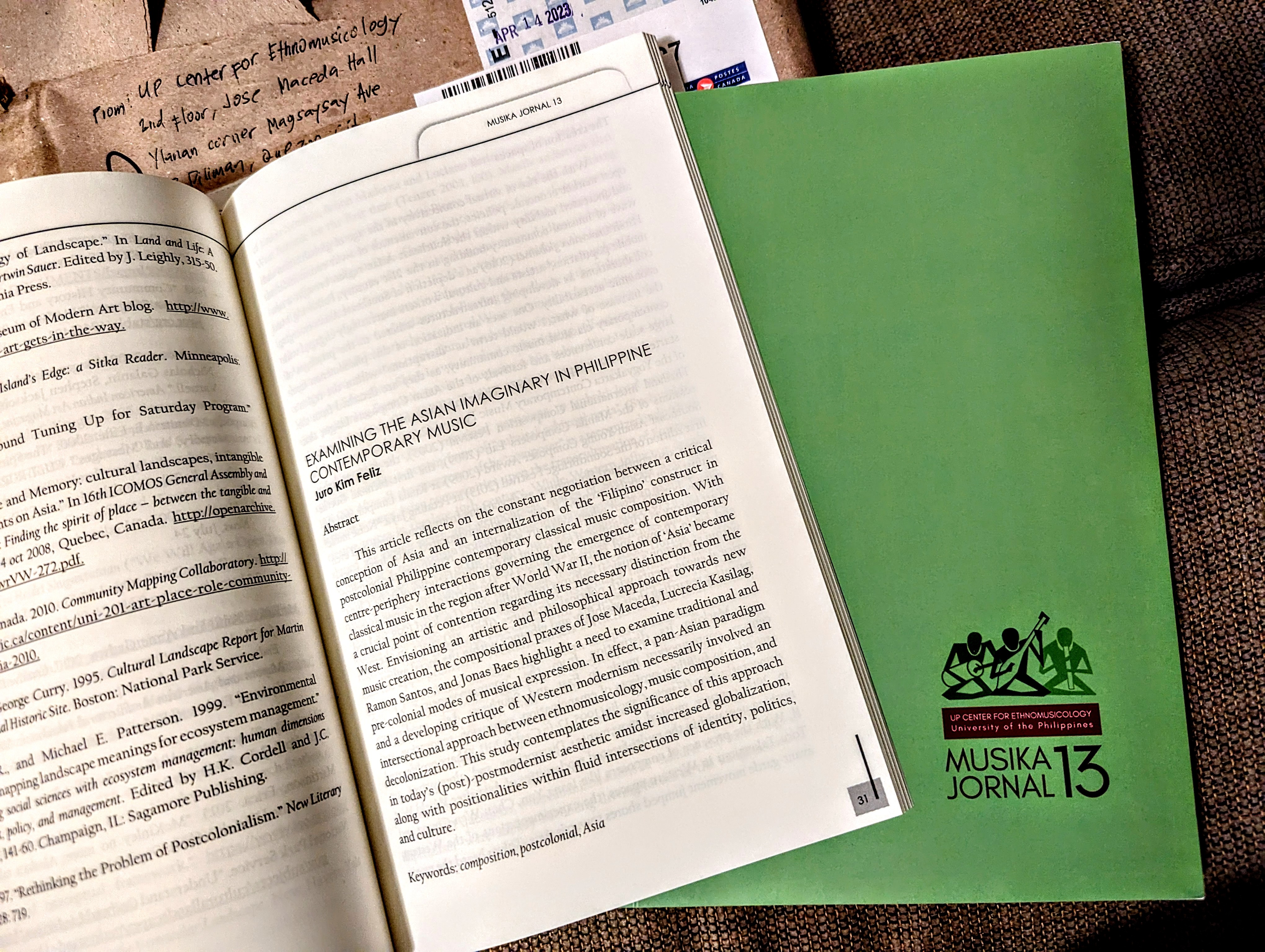

- Publication of “Examining the Asian Imaginary in Philippine Contemporary Music” in Musika Jornal 13

This journal article is my first academic publication. It was seven years in the making, back when I first started research during my studies at McGill University. Dissatisfied with graduate course offerings during my second year, I proposed my own research project instead that focused on contemporary music in Southeast Asia. It was a no-brainer back then, and it’s sadly the same way today: mainstream contemporary composition studies in the West ignore histories, practices, and sociological contexts coming out of our part of the world. This happens even as Filipino composer Jose Maceda, among other older Southeast Asian composers, had laid down significant foundations for today’s (post)avant-garde/(post)postmodernist music making in the region after the 1950s. Not to mention that hegemonic Western modernity has taken hold of shaping the region’s present and future. Not to mention that the emergence of ethnomusicology as an academic field hugely informed the way Filipino composers found their ways to decolonize their practice. As if to contradict European avantgardism, I will always quote Ramon Santos in saying, “What is the meaning of being avant-garde? In the Philippines, it means becoming primitive, covering non-Western sounds” (Somtow Sucharitkul, “Crises in Asian Music: The Manila Conference 1975,” Tempo New Series 117 (1976): 21).

I initiated this research project under the supervision of composer Melissa Hui and musicologist Roe-Min Kok. The UP Center for Ethnomusicology provided research materials, including scores for Jose Maceda’s Pagsamba (for 250 performers in a circular space), Music for Five Pianos, and Ramon Santos’ Parangal kay S. W. (for gamelan and orchestra). Polishing the article years after finishing my Masters degree at McGill, Musika Jornal accepted it for publication in 2018 and finally published it in 2022. Framing composition practices within musicological and sociopolitical contexts was a scholarly task worth pursuing especially for postcolonial societies like the Philippines. But much more needs to be done — this invisibility is injustice long left unaddressed.

“Examining the Asian Imaginary in Philippine Contemporary Music” is now out on Musika Jornal 13! Click HERE to get a copy.