[N.B. The year 2024 has been a whirlwind of action for me, resulting into a lack of writing in this space since the last post in 2023. This post is my way of remedying that absence. I should make it a New Year resolution to write more thought pieces here. I’ll wrap up everything in a year-ender post soon anyway.]

I picked up Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of my Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (2014) two months ago. The narrative of “Filipino/x invisibility” strongly permeated my thoughts for the past years, but a music conference I took part in Montreal in May 2024 got me learning about “hauntology” for the first time. Filipino-American writer Oscar Campomanes nailed it in conjuring the phrase “spectre of invisibility,” when ghostly presences inform and materialize our invisibilities. I feel this resonates loudly with the career I have been pushing for a decade and a half. I still roam like a ghost, emitting whispers that should have been deafening screams.

Two months later, I am nowhere past my first sixty pages of the book. I have to step back and soak it all in. (I had to finish writing a book chapter on Filipinx invisibility anyway, hopefully out in a publication of writings on socially-engaged art in mid-2025).

Taking off from Derrida’s 1994 conception of “hauntologie” (a spooky play on “ontology” — unpacking modes of “being/existing”), Mark Fisher frames certain paths and hauntings music has taken in the last fifty years. Capitalist realities that dominated the turn of the 21st century pried windows open to invoke lost futures and create their conjurations. Derrida originally noted that (“Second World”) communism has been repeatedly conjured and caricatured enough like a ghost to convince the world of its seemingly logical demise. So where were the promises of progress since Kraftwerk, punk music, and modern technologies? The nostalgia modes found in the likes of Arctic Monkeys and Amy Winehouse’s song Valerie (2007) instead conjure fictional anachronisms that neither operate in the past nor the present, Fisher argues. The sense of future shock has disappeared in the 21st century, as mainstream music cultures retained forms so recognizable even to those from fifty years ago. Fisher calls it the “slow cancellation of the future.” The future is cancelled. Next!

Fisher isn’t with us in this world anymore to see the implications of AI and increasingly pluralistic directions from select parts of the globe. This even off-key reminds me of a friend joking about her need to tell long-dead Theodor Adorno about Tiktok. *insert shrug emoji here* *follow it with a laughing cat emoji while I’m at it* *another emoji of Adorno waking up from his grave, perhaps?*

While I’m critical of this insistent, Western story of cultural “progress,” there’s definitely merit to Fisher’s assessment of anachronisms and hauntological imaginations. Even the proliferation of synthwave music today to me is a strong case of American-rooted (even “-centered?”) nostalgia to “escape” rather than “move” towards the imagined dystopian futures of pop culture. This nostalgia is a “feel good” consumer-friendly kind, the way you would remember your childhood and how it used to be better in the good ol’ days. (Believe me, I can do the same though with the likes of Alison Krauss of the 1990s and dreamy visions of Metro Manila streetscapes). It would fall outside Fisher’s hauntological music that conjures ghosts to challenge the inevitability of today’s production field. “These spectres — the spectres of lost futures — reproach the formal nostalgia of the capitalist realist world,” he writes. But it doesn’t matter to me for now. Similar modes of production become fodder for imagining alternative futures apart from the constant replications of doom and destruction within grand narratives, whether of (post)modernity or of (post)capitalism.

Then there’s the postcolonial and diasporic position. I’m not entrenched in ways of moving and thinking that the Global North-slash-“First World” embodies. Poverty and colonial mentality have dominated the minds of Filipinx generations at home and abroad. They stand as the sun, and we planets orbit around them. We try with all our might to escape gravitational forces. And yet people don’t escape its influence even when they manage to eject themselves outside the system. Current events, politics, and struggles of friends and family would always encroach and pull us — those who maintain ties to the homeland — back into that space. One can trace dysfunctional cultural mores and politics within Filipino society to generations of foreign colonial systems that have determined, and still continue to determine, the movements and futures of peoples.

These are some of the ghosts that inform Filipinx invisibilities. Others have determined our futures for so long that the ones we conjure merely fall into neoliberal-centered worlds that former colonizers have long defined for us. One very good example I know is this rhetoric of “world-class” among arts in the Philippines. What is this “world-class” aspiration? Instances of this always involve music and theatre, where imagined standards create institutional simulations of classical concert halls, Broadway musical productions, artists gaining international prominence, and those reflecting the technological modernities and approval of the “West.” People see a thing so professionally well-done and exclaim, “This is ‘world-class!'”

For the Filipino middle-class, “world-class” is the polar opposite of local grassroots amateurism and the bastardized, parochial “bakya” of local mainstream media. (Traditionally meaning rattan sandals worn by women, the “bakya” turned synonymous into being cheap, having bad taste. Read: being local). Do people really have an accurate view of the world when they use this rhetoric? Moving to North America, I look at diverse music scenes and think, “Hey, this is ‘the world’ as you know it. This is what they do here!” I listen to, say, improv sessions or Sufjan Stevens’ album Michigan (2003) and think, “This sounds so janky and wonky, the Filipino establishment would never call this ‘world-class!'” And yet with ten solo studio albums and more, Stevens has amassed audiences with hundreds of millions of Spotify stream counts and nominations from the Grammy and Academy Awards. Improvisation practices captured contemporary music scenes in its empowerment of musicians beyond an “authorial/composer” voice. I wonder how often this myth of the world, embodied in the so-called “world-class,” becomes heavily misplaced in that to me, it stands as a caricature of class, social mobility, and colonial mentality. The world is more pluralistic and multidimensional than colonial versions of European concert halls, pristine tech-studded productions of Broadway musicals, and celebritification of artists whose traces of Filipino ancestry, however few and slimey, are the rave of the people — all ultimately serving the neoliberal economies and consumerist productions of the Global North.

As Filipinx inner lives are invisible to the global mainstream, the possibilities of Filipinx futures are made invisible and even limited with colonial aspirations. Sometimes, I think of it as the long-running conundrum of speaking the colonizer’s language in order to be understood. Passing off through recognizable forms of Western modernity is an unfortunate strategy, lest the Filipino falls back into being the Othered, savage indio (“Indian,” as the Spanish eventually called the natives). Maybe Frantz Fanon, who wrote Black Skin, White Masks (1952), could still teach us a thing or two here.

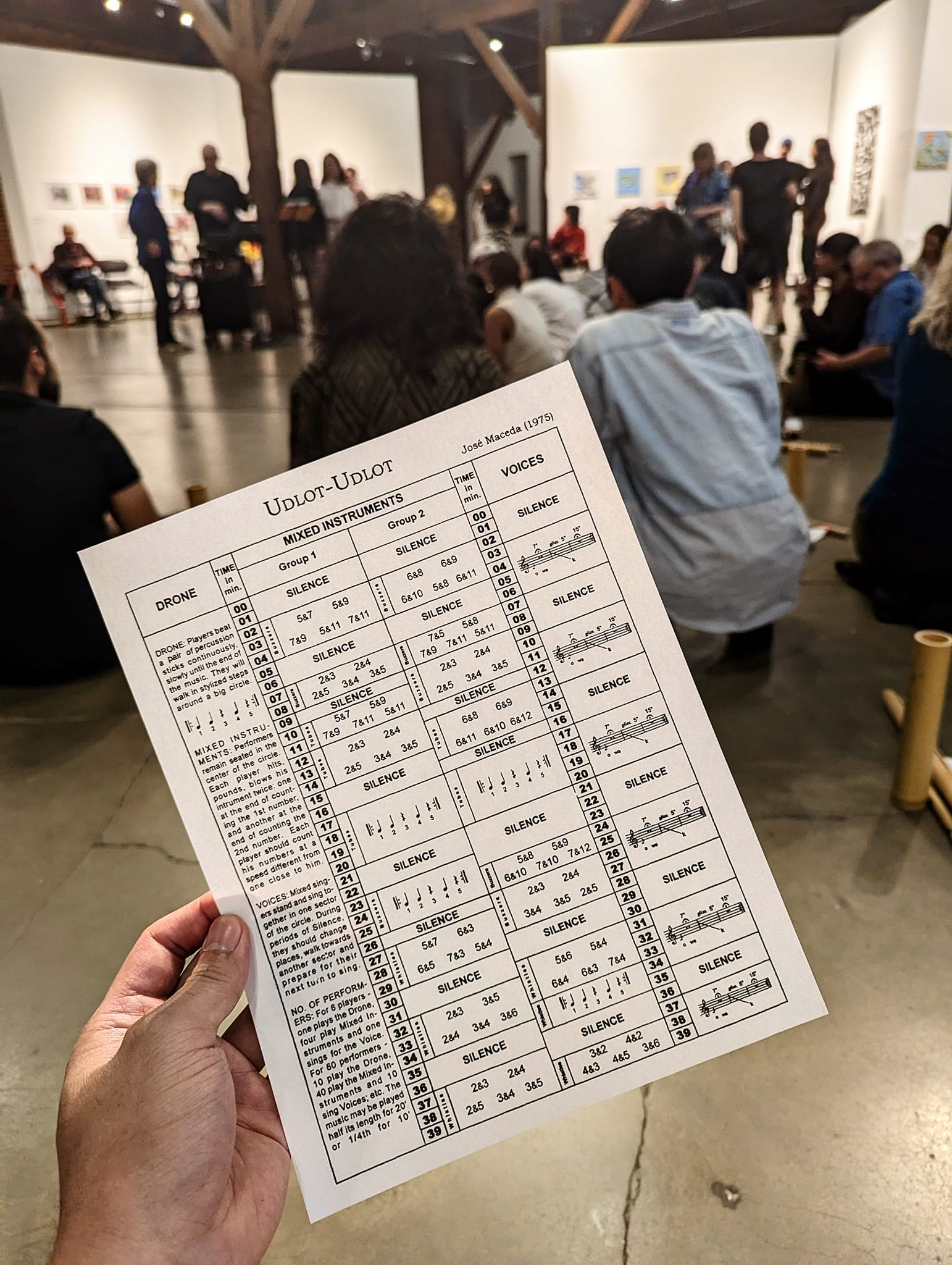

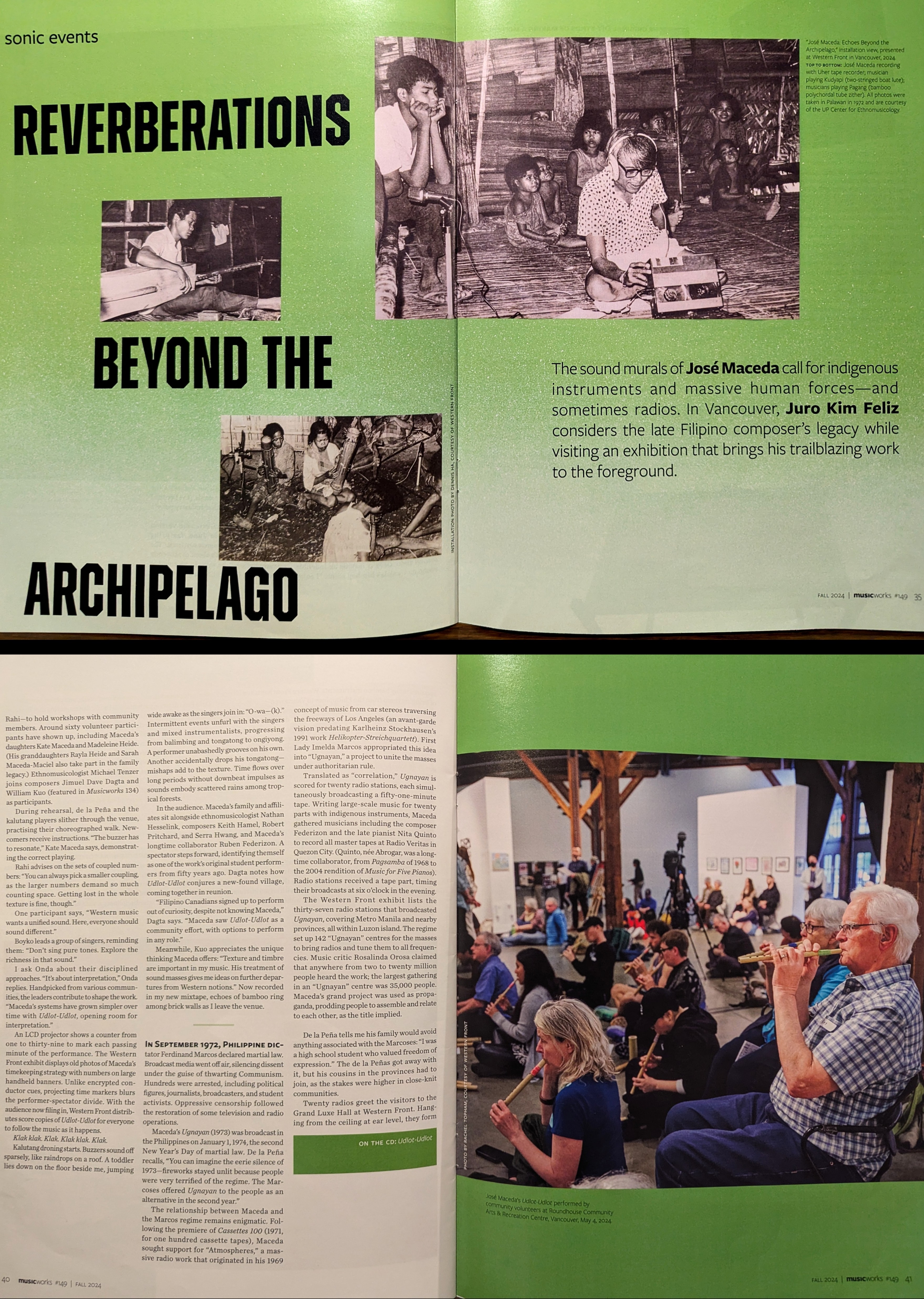

Hauntings of pasts and futures collided when I wrote my Jose Maceda magazine feature for Musicworks, published in Fall 2024. Artist-curator Aki Onda and Vancouver-based Western Front presented a months-long exhibition on Maceda’s legacy in May 2024, fronted with the Canadian premiere of Udlot-Udlot (1975) and a radio installation of Ugnayan (1973). [Shameless plug: Get a copy of Musicworks Fall 2024 issue to learn more. ;)]. Conditions were not in my favour, but presenting an academic paper in Montreal (on Filipinx invisibility, no less!) and teleporting to Vancouver the very next morning to do fieldwork was tremendously serendipitous. Moreover, Maceda, a Filipino avant-garde composer and ethnomusicologist, posthumously started to garner visibility among the international contemporary music scene. (Quite too late, in my opinion). Julian Cowley wrote a magazine feature for The Wire in 2019. Kate Molleson, who facilitated the music journalism workshop I took part last year at Darmstadt, published her book of long-ignored contemporary composers (Sound Within Sound: A Radical History of Composers in the 20th Century, 2022) that includes a chapter on Maceda.

Maceda profusely engaged with decolonizing Filipino musical life through colliding indigenous music and European avant-gardism when a language hardly emerged for it in the 1960s. (To put in perspective, Edward Said published his book Orientalism that pins down the Western perversity of exoticism in 1978). But I also find Maceda embodying what musical futures could have been in Southeast Asia. The futures he envisioned dealt with haunted pasts of erasures, as the newly-found discipline of ethnomusicology in the Philippines strived hard to document hundreds of indigenous traditions nearing their extinction because of encroaching Western modernity. (The same way encroachments of neoliberal development took over ancestral lands and natural resources, we may add). My editor first questioned me when I wrote of Maceda “turning his recorder toward echoes of lost musical pasts.” She grilled me: Are they really “lost?” Or maybe just “disappearing?” Do we really need the word “lost?” I doubled down — yes, of course. Travelogues and European writings took account of musical activities in the islands that have already vanished, including the presence of gongs in the lowlands and the noise making of villages during lunar eclipses. The “island pasts and futures” I framed in the Musicworks magazine feature relate to this legacy of reimagining alongside salvaging this loss. And yet, the kind of music, mode of production, and philosophy Maceda espoused never fits in with the “world-class” aspiration that the Filipinx middle-class status quo currently pushes.

Behind the scenes, the Canadian premiere of Udlot-Udlot in May 2024 also converged pasts, presents, and futures like a melting pot: Maceda’s family members and friends, colleagues, composers, ethnomusicologists, and just the curious general public, Filipinx(-Canadian)s and otherwise, who both performed and sat at the venue. I can’t deny an appropriated sense of familial attachment when we say, “This is our lolo Jose.”

The only time Maceda and I were in a room together was the time I turned pages onstage for Nita Abrogar-Quinto during a concert performance of his Music for Five Pianos (1993) in 2004, the last performance Maceda probably attended before he died months later. I was a first-year student at the University of the Philippines College of Music back then. We never met. I can only dream of making his acquaintance in 2004 with my future self twenty years later.

If Mark Fisher was into avant-garde music, would he take heed of the hauntologies and lost futures Jose Maceda’s work conjures now? I’m not really sure. Citing the sociologist Paul Gilroy (Postcolonial Melancholia, 2005), Fisher feels the need to distinguish “hauntological melancholia” from “postcolonial melancholia.” In Gilroy’s framing though, postcolonial melancholia refers to the colonizers’ painful evasions of dealing with cultural and imperial histories. This speaks of the former colonialist-imperialist position, extending to the ways white-dominated societies now deal with the social effects of globalization, immigration, and increasing multiculturalisms and pluralisms. This doesn’t speak to the melancholia of the colonized! Where’s the migrant, the immigrant, the diasporan subjected to these histories and resulting migrations? Their melancholia also conjures nostalgia of lost futures! Philippine society has a version of what-aboutism too — what if Spanish and American colonisation never happened? (One popular hypothesis speculates that the Philippines would have been a Muslim country instead, with the encroachment of Islam down from Indonesia and the sultanates of Southern Philippines).

The spectre of invisibilities lives on for now. But so is the capacity to conjure lost futures to make new ones.