Endless persisting with fevered dreaming

Juro Kim Feliz

(part 4 of 5)

N.B. This is the fourth of a series of five essays around the release of Liham: A Digital Song Cycle. Listen to the art song with fevered dreaming here: https://www.lihamproject.com/with-fevered-dreaming

Dear Reader,

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment when I first learned how to swim.

We were victims of house fire just as I finished kindergarten. My grandparents’ house in Camarin, North Caloocan burned down due to electrical faulty wiring during a blackout. It was a multi-generation, multi-family home, with our family, aunt, and uncle’s younger family living with my paternal grandparents — my grandfather was largely absent then as an overseas worker in Saudi Arabia. Recovery was rather quick for us — it wasn’t long before our little family purchased a small bungalow house in a subdivision in the far suburbs north of Metro Manila.

The subdivision was newly constructed when we first moved in. The amenities include a clubhouse on top of a small hill and a swimming pool, which I took interest in fairly quickly. We were soon enjoying our time with parties or a simple afternoon of swimming whenever we could afford to. My father would tell people that I taught myself to swim by observing others, from dog paddling and touching the pool’s deep end to front crawls.

I tried ice skating less than two decades later. The irony of doing it in tropical Manila isn’t lost on me, but one of the big malls used to have an ice skating rink for enthusiasts. A friend happened to be one, who invited me to join her. It was a very foreign and painful experience to balance your feet on thin metal. Anyone who swims or does ice skating will tell you to let go of the side railings to truly learn. But I desperately clung to the sidelines instead. It was the opposite of swimming — a real sensation of gravity felt more dangerous and injury-prone than the security of buoyancy on water.

Embracing foreignness takes courage.

The Philippines sits in the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire, where geological processes unfold with convergences of tectonic plates around the Pacific Ocean. My toddler years weren’t spared from earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. A devastating earthquake afflicted northern and central Luzon (the largest island) in 1990, causing massive property damage and claiming thousands of lives. Mount Pinatubo erupted the next year, disrupting the lives of my maternal grandmother and relatives among hundreds of thousands who resided close to the volcano.

But these catastrophes don’t happen regularly. Instead, one watches out for the annual monsoon winds and sprouting low-pressure areas that bring hordes of typhoons and thunderstorms. As of this writing, typhoon Emong brings a new onslaught of strong rains in Northern Luzon just as typhoon Crising recently wreaked havoc with flooding and landslides a week before. Manila itself is a catchbasin — paired with urban planning failures and mismanagement, flash floods are a way of life.

Right: The final massive eruption of Mount Pinatubo among a series of eruptions in June 1991, photo by Albert Garcia (source: Daily Tribune PH).

A popular narrative of resilience abounds with the normalcy of socio-cultural conditioning against storms and tribulations. Urban dwellers find humour and disdain in being “water-proof” — braving the streets to go to work amid huge downpours with little recourse. An adage surfaces: “Pag may tiyaga, may nilaga.” Perseverance ultimately bears fruit to all labour. Curiously, “nilaga” refers to boiled stew or other food like eggs. In other words, endurance begets food. Survival.

Moving into the North American diaspora, this cultural expectation of resilience drives Filipinos to endure unfamiliar territory. Exchanging the familiar for the strange is disorienting, but the promise of freedom is greater. One is expected to let go of the sidelines and swim dangerously in deep waters. Hard work is the so-called key to success. But despite popular wiles, Yen Le Espiritu (2004) challenges advocacies that merely justify immigrants as assimilable and equally hardworking as native-born folk. Doing so avoids questioning why white middle-class culture is superior and mainstream — both in Canada and the United States, as I add into the argument. Why subject people to less privileges as they are forced to conform and naturalize into whiteness? Then they get “othered” when they don’t manage? Modern-day imperialism comes into mind.

They say we’re supposed to be resilient.

Moving abroad is popularly considered a “class-equalizer” in the Philippines, but it’s also an illusory perception. The educated well-to-do move elsewhere with safety nets, family support, and a bail-out plan in case things don’t go well. The lower middle classes get lesser choices and fewer assurances, if any. Consequently, expectations of resilience are higher among them. Bonnie McElhinny et al (2012) notes the diverging socioeconomic classes of Filipinx migrants according to Canadian immigration policy phases from the 1960s onwards. Earlier Filipinx migrants were white-collar, middle-class professionals. A shift happened later towards the influx of working class migrants. While we talk about resilience and hardship, some immigrants really just had it easier. The rhetoric of resilience also has uneven terrain, like hills standing high and dry amid those stuck in submerged lowlands as the rains pour down.

I turn to Francisco Santiago’s kundiman Anak Dalita (1917, merely named originally as “Kundiman”) in pursuing this point. While kundiman has existed in popular forms at the turn of the 20th century, Patricia Brillantes notes in the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art (1994) that Santiago’s “Kundiman” is considered the first art song-style kundiman. Within classical music’s means of production, formalizing the kundiman also created an expression deemed “Filipino” and, therefore, “anti-colonial.” This proved a precedent that composers like Nicanor Abelardo, Bonifacio Abdon, and Constancio de Guzman followed in the 1920s.

Anak Dalita hints at precursors of class struggle — only hinting, because it acknowledges the condition of destitution while romanticizing the “helpless victim” trope who needs saving. Departing from Jesus Balmori’s Spanish poetry, Deogracias Rosario’s Tagalog prose cuts through, straight as an arrow: “Ako’y anak ng dalita // At tigib ng luha // Ang naritong humihibik // Na bigyan ng awa” (I’m a child of destitution // Full of tears // Who comes pleading // For needed sympathy). The motherland’s colonial tribulations mirror the people’s sufferingamid enslavement and poverty. The shift to a major key midway creates the rhetoric of hope and freedom. The kundiman’s musical form is deliberately designed, inadvertently harbouring the vindictive, revolutionary godhand that would sweep judgment and justice over the land.

But resilience embodies a bigger story of class struggle.

Remembering Le Espiritu, one surmises that formalizing the kundiman relied on assimilability – liberating and migrating the native from a perceived inferiority to match a superior mainstream. It’s about meeting colonizers eye to eye and being seen as equals, dictating the emergence of Filipino modernism in the next decades under American rule. But we have already established that this only shows a unidirectional move – the colonizers remain on top, while we are expected to strive and reach them without questioning why we should.

And yet, I search for YouTube performances of Anak Dalita and find singers wearing fashionable Filipiniana and barongs out of national pride. The middle class now proclaims, “Ako’y anak ng dalita” (I’m a child of destitution). Just like the classical arts, the archaic kundiman is now detached from the people it represents. I’m not calling for petty prescriptive performance attire to render “authentic” performances. But it’s this exact performativity that sets aside a more pronounced positionality. It’s no longer feasible to treat operas like Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (1904) as mere performances while ignoring orientalist sins. My argument is, commodifying the kundiman enabled the privileged to co-opt expressions of poverty at whim to perform nationhood. This nuance is masked for the Filipino, as the nationalist’s interest of solidarity is at stake here.

It’s striking that liberation from Spanish rule played out similarly. As the Paris Treaty of 1898 threw Philippine independence under the bus, the educated “mestizo” middle class eventually betrayed the native revolutionary movements in favour of a more convenient American takeover. The reasons are obvious: it’s non-violent, it preserves feudal structures that benefit land owners like them, it maintains a status quo. This betrayal threw away leadership and even the lives of Andres Bonifacio, Antonio Luna, and others. The enduring rhetoric of resilience now begs the question: how come the lower-class folk are goaded into resilience while the powerful sit comfortably?

“Don’t hold a grudge against snow and ice.”

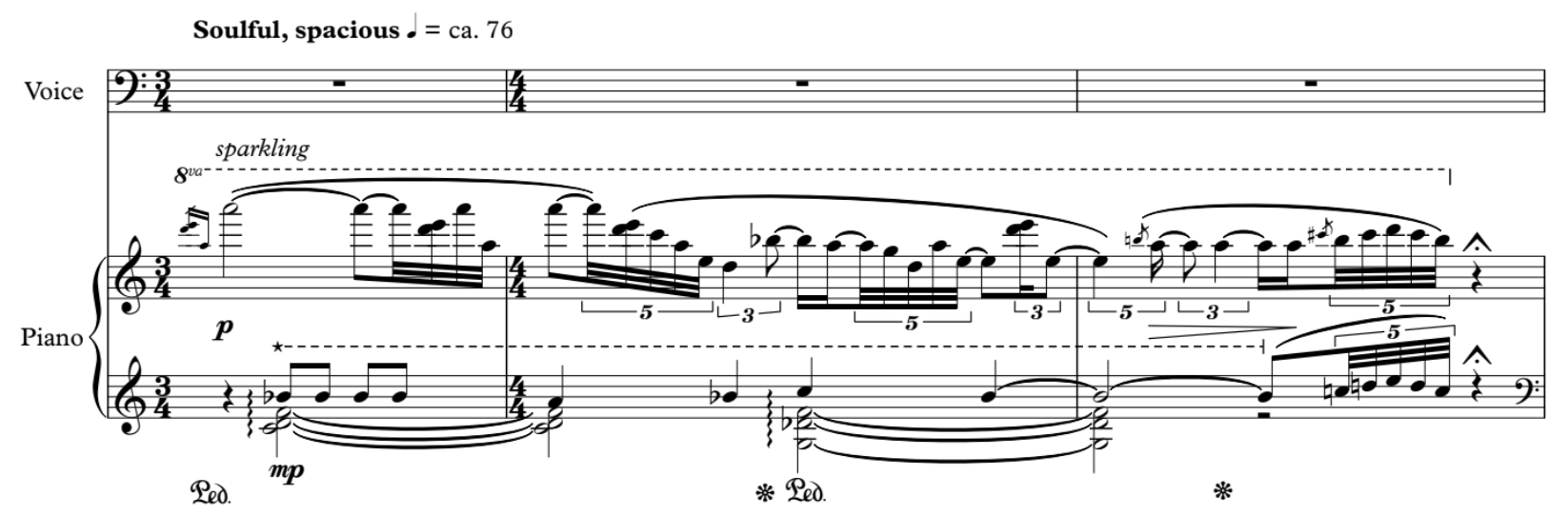

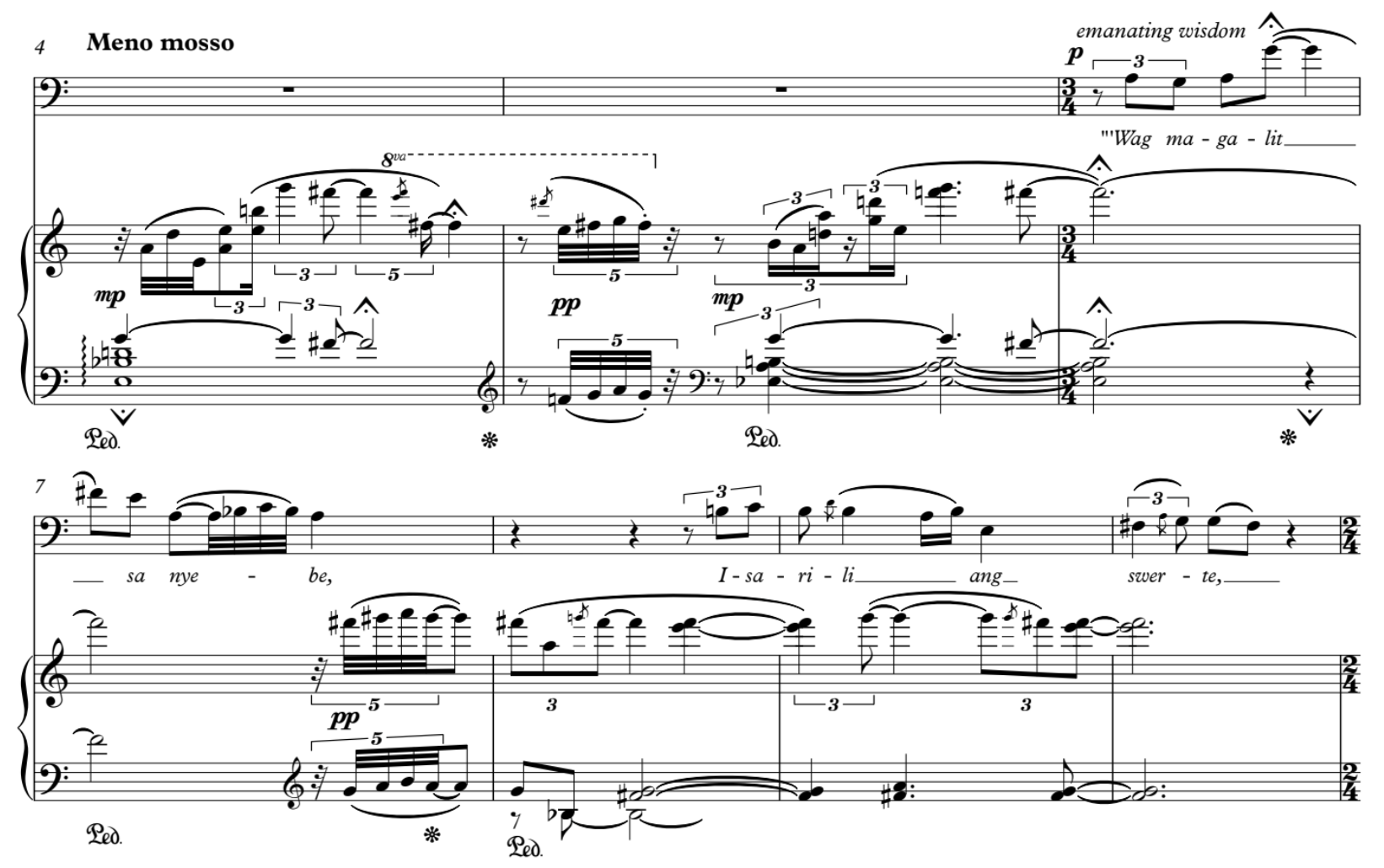

The song cycle Liham continues its saga of positioning Filipinx lives and bodies — with fevered dreaming is its third art song, setting a diasporic, poignant mise-en-scène of icy roads and homesickness. This is no surprise to me as Revan Badingham III resides in Montreal (as I did for a number of years) with the normalcy of its cold winters. Their libretto houses a rondeau redoublé, a poetry form of 25 lines grouped in quatrain verses that produce circular oscillations of images like the insistent refrains of the second art song’s villanelle. Remembering the lamento structure of the song cycle, we now stand at “B-flat.” A parallel world (seen on the piano’s sparkling right hand melody) orbits on the note “A,” a minor second below/major seventh above.

(Read “Entering the worlds of Liham” to know more about the song cycle’s overarching lamento motif structure and its worlds, pitched a semitone apart).

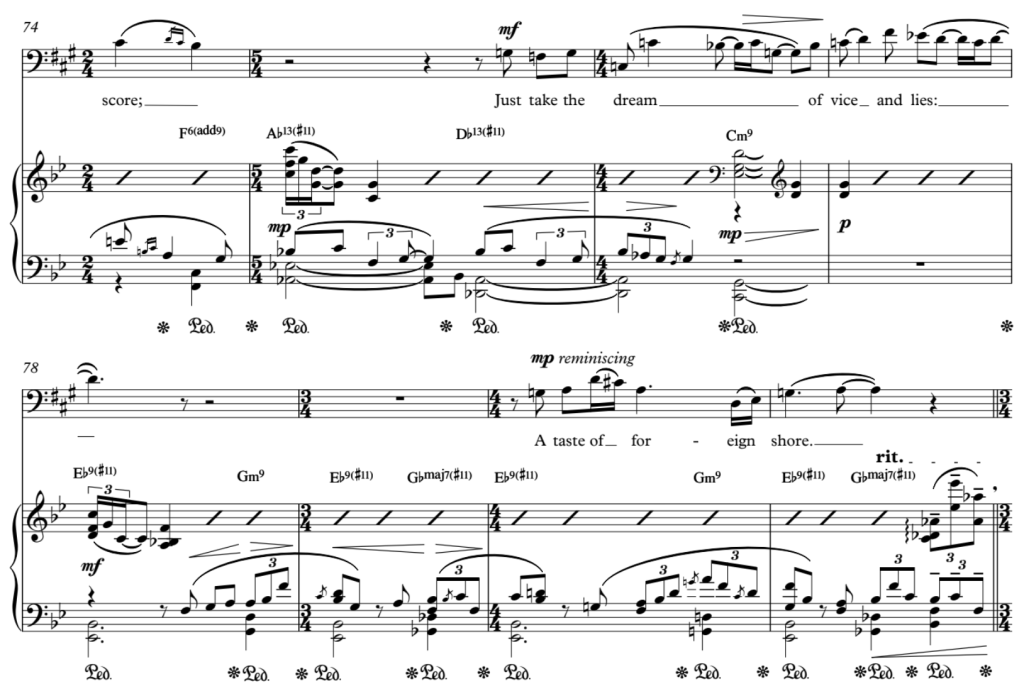

The first three bars of with fevered dreaming. Instead of the original F minor key, the kundiman Anak Dalita plays out on a B-flat major key.

In a twist of deceptive positivity, the introductory melody of Anak Dalita rings out in B-flat major on the art song’s first three bars. The original key is in F minor. This transformation alone is contrived in nature – the hurting Filipino smiles outwardly as a conditioned response. “Kapwa” and its shared identities have a way of conjuring conditioned responses. The individual is subject to the collective good of others around them. In a world of climate disasters and calamities, dragging everyone down is unnecessary and considered selfish.

Badingham’s introductory tanaga echoes this further: “‘Wag magalit sa nyebe // Isarili ang swerte” (Don’t be mad with the snow // Keep luck to yourself). The long-time immigrant admonishes the newcomer not to blame things beyond one’s control. In the same breath, such pronouncements also make the argument of not questioning one’s precarity. “This is how things have always been,” they say — “there’s no use in complaining about it.” The collectively conditioned delusion of helplessness takes over as the tanaga continues: “May kurba ang tadhana // Hindi ka mawawala” (Destiny has contours // You will not be lost).

“Pagtitimpi” translates as temperance or suppression – however you want to define it.

This Tagalog word refers to a virtue of moderation, of controlled countenance, of putting a lid on things. No matter the circumstance, one’s lips should remain filtered and sealed. Saying the word itself creates a visceral feeling of literally keeping lips close together — the /m/ consonant further tempers scattered, insistent /i/ vowels throughout the word. It effectively conveys that calculated sobriety maintains social harmony, while tactless maneuvers only sow discord that invites bad luck. Respect to the elderly avoids antagonizing and disparaging them. Indirect forms of communication avoid confrontations and upsetting a group.

It’s interesting how ambiguous this seemingly simple imagery stands. The attitude toward temperance is of exteriority – maintaining order lubricates social harmony in the outside world. Suppressing individual feelings and needs doesn’t matter. Sacrificing oneself for the greater good outweighs the burden of one’s chaotic internal world. This is where a trauma of resilience starts: there’s another mouth to feed, there’s a social expectation of prosperity out of hard work, there’s an exterior image to maintain. In spite of what we truly feel, there’s no choice but to bottle it up and press on, lest we die.

There’s another Tagalog word in mind here: “ngitngit” (/ŋit-ŋit’/, gritting one’s teeth). The first sung line of with fevered dreaming forcefully imposes a gritty feeling. A high baritone is expected to sing and hold a high G right on an /i/ vowel in the word “magalit” (angry). The word-painting grit of keeping a high tone on a suppressing vowel immediately yearns for a release that is denied throughout the whole art song. For the freezing migrant, there’s no room for respite. What matters is, they can survive the winter and live another day.

Icy roads change the way you walk.

My first years in Montreal taught me that slipping on ice is something you don’t resist. Fighting your body only results in injury. Learning how to ice skate involves learning how to fall properly — don’t extend your arms and elbows to catch yourself, let yourself slide to minimize impact, avoid falling on your head. Transferring that mobility to snowy roads, you change walking patterns to shift your centre of gravity further forward and glide through instead of pushing yourself backward for forward momentum like on regular surfaces. (And of course, wearing shoes with higher ground traction is a default).

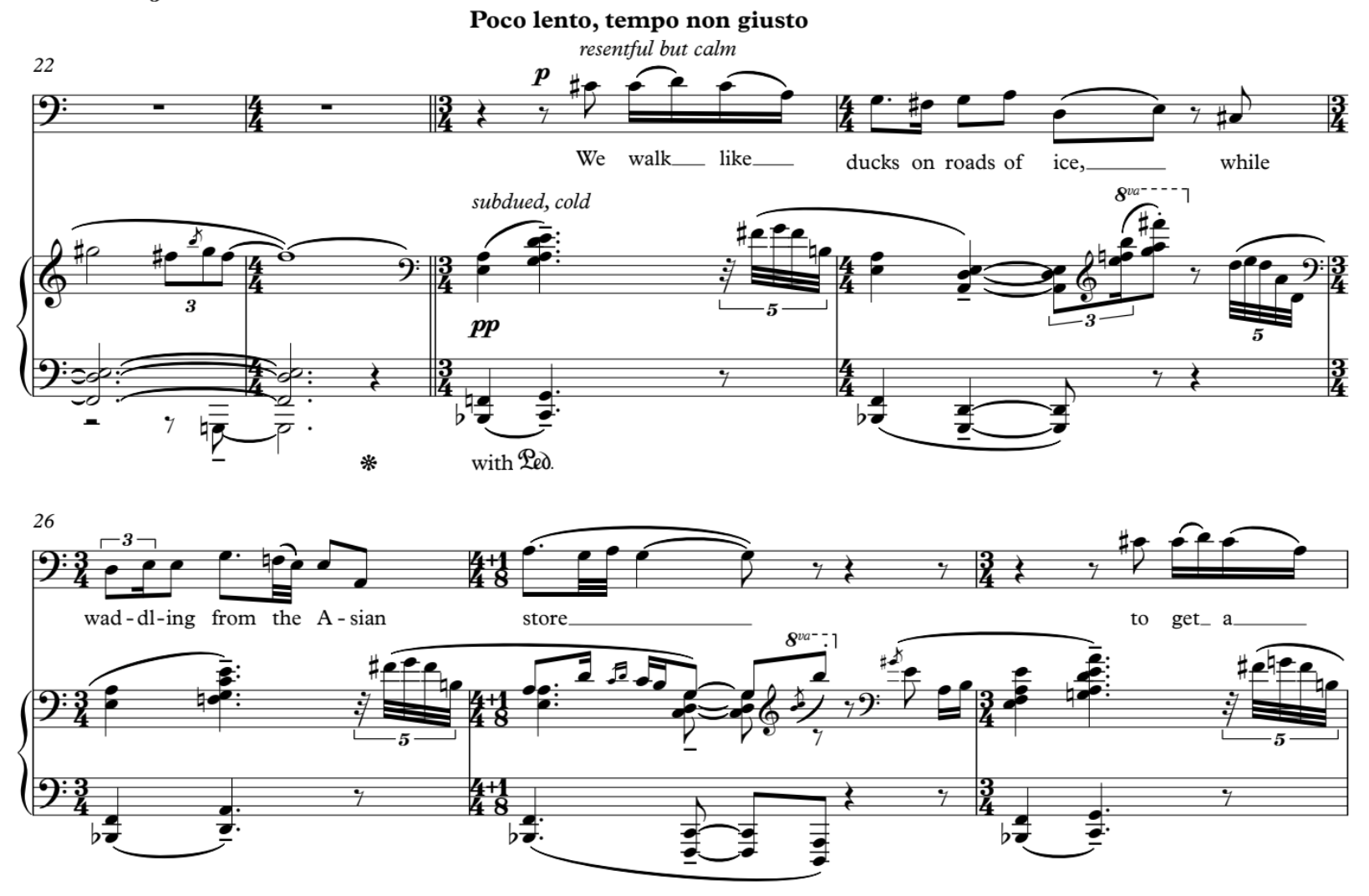

Badingham’s rondeau redoublé for with fevered dreaming iterates refrains derived from all lines of the first quatrain verse: “We walk like ducks on roads of ice // While waddling from the Asian store // To get a sack of Jasmine rice // A taste of home on foreign shore.” Badingham’s resilience has a face: it’s the forbearing migrant who strives to earn a living, enduring winters while shopping for basic necessities and a nostalgia for home. One exchanges the familiar tropical contours of home with the strangeness of freezing lands for the greater good. They walk in lockstep with awareness of their precarity as harsh environments become the litmus test of their resolve.

Of all the art songs of Liham, this third one contains music that has the most straightforward rhythmic pulse that unites both voice and piano. Triple metre pervades these refrains and sets a walking pace. Stretching the second beat doesn’t always translate to a waltz — a calculated unevenness drags the pulse like cautious, dragging feet lest a misstep causes a slip on the ice. We hear the rhythmic motif of a duck walk. Creating more varied unevenness from this motif pries a landscape open and stretches it, akin to characterizations of sparse Canadian landscapes. Observing this emerging correlation between geography and the music of Canadian composers, Elaine Keillor (2006) notes an encultured understanding as Hungarian-born Istvan Anhalt internalizes Canada’s disjunct, expansive territories in his music. During my studies at McGill, a percussionist described this attitude succinctly to me: “Canadians love their space, literally and figuratively.”

But such articulations of space carry far more nuance. with fevered dreaming evokes a gripping image of precarity out of a sack of Jasmine rice. White steamed rice is sustenance for the average Filipino. In contrast, deadly winters in most of Canada are a fact of life. Far from inevitable daily commutes in the Philippines, walking out during winter is also part of Canadian city life, especially if you simply live within a 10-minute walk from a grocery store. Dragging one’s feet in the snow suddenly turns into one of survival and homesickness. It’s not a stretch to imagine someone dashing out under below freezing conditions, sometimes under battering snow storms if need be, to feed themselves while longing for a taste of home that they left behind. I can imagine my mother in such situations — she who first moved to Canada and paved the way for the family (not including me) to move ten years later.

I always marvel at Toronto’s skyscrapers whenever I take a ride by the Gardiner…but not today.

Taking a rideshare feels like a waste of money, even when necessary at times. “I declare today’s ride ‘necessary!’” I grumble as the 15-kilometre route from my Weston neighbourhood wriggles its way through Toronto traffic. This time, algorithms refuse to give the Gardiner Expressway route that would double the distance without significant time gains. Emerging out of Davenport Road’s craziness, the drive takes me through the Rosedale ravine toward the Don River — “Toronto’s backdoor,” as I call it, like we’re sneaking through the desolate backyards of towering downtown buildings.

I finally arrive at a dumpling house in East Chinatown, where Carolyn Fe waits for me and my recent MacDowell artist residency stories. Finishing lunch, we make our way to Supernova Coffee around Broadview and Danforth. Carolyn spills the beans: “We moved to New Hampshire when I was seven or eight, thinking that we’re gonna stay in the States.” There was even talk of Texas. I think my ears tingled. “Of all places, why Texas?” I ask. Without flinching, she responds: “The ‘Murican dream!” Her humour is on point — I crack up as she mockingly wears a contrived heavy American accent.

The American dream didn’t happen. It was in Montreal where I first met her as an established singer and actor. But looking back at my interview with her, I wasn’t surprised at hearing this persisting narrative of Filipinos chasing the American dream. A BusinessMirror newspaper editorial (January 2019) notes the Filipino’s fondness of imported American goods, labeled as “stateside” products during the 1970s. The United States was always a first choice for Filipinos seeking studies or work abroad, so much so that Ryan Caybayab composed Not All the World is America (1989) for his now-defunct singing group Smokey Mountain. That trend continues even with the awareness of present-day American authoritarianism, pulling all sorts of unlawlessness to evict brownness out.

“We never ask the bargain price” — but it’s never enough to pay the price in full.

Filipino culture normalizes submission and servitude. The notion of “kapwa” emulates this golden rule of treating others like you want to be treated. (I wrote about “kapwa” in the third essay “Marching child of the sun revolting”). As you bestow obedience and loyalty to those above you, you would demand the same from the next generation. This frame of respect and authority feeds ongoing feudal structures, inherited from centuries of Spanish colonization. It partly explains why questioning authority has real-life consequences, like losing your job, being branded as difficult, or being accused of rebelling against religious institutions.

Carolyn Fe’s Living Letter describes her experience of hard bullying as she grew up in Laval, Quebec of the 1970s. She recalls: “We didn’t even have black people then — brown literally showed up, the school went, ‘What the fuck?’” The Otherness of everything Filipino was the subject of white juvenile ridicule. But instead of cowering down, she justified and fought for her achievements. During the interview, Carolyn attributed this learning to her abandoning religion. “Catholics are taught to fear God.” (Roman Catholicism is another inherited Spanish legacy). “It didn’t make sense – why should I fear God? They’re hurting me.”

Her Living Letter leads me to Edward Said’s essay “No Reconciliation Allowed” in Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss (1999, ed. André Aciman). Early on, Said realized his Otherness as a Palestinian kid in Egypt with an English first name and an American passport. He got an Anglocentric education at Cairo’s Victoria College, a school meant to educate ruling-class Arabs after the British left. And yet he writes: “I was also trained to understand that I was an alien, a Non-European Other, educated…not to aspire [being] British.” With Said’s expulsion (due to his trouble-making) also came the old Arab order’s crumbling in the 1950s. Transferring to a school in Massachusetts jumpstarted an American life, fraught with the burden of justifying Palestine’s existence and his own politics.

One fights against erasure – holocausts and genocides aside.

Colonial agenda always seeks to erase and replace things with those that further enable and propagate themselves. It’s the supremacy agenda that keeps rolling wheels in perpetual motion. (I wrote about “white supremacy” in the second essay “Mapping the land of the mourning”). At this time of writing, Israel’s horrendous crimes of genocide aim to erase Palestine and fulfil its ethnostate aspirations. On a related note, aspirations and the dignity of Filipinx migrants are constantly on the verge of erasure within white supremacy, as the status quo keeps them in their proper places. What is a rational response to such threats?

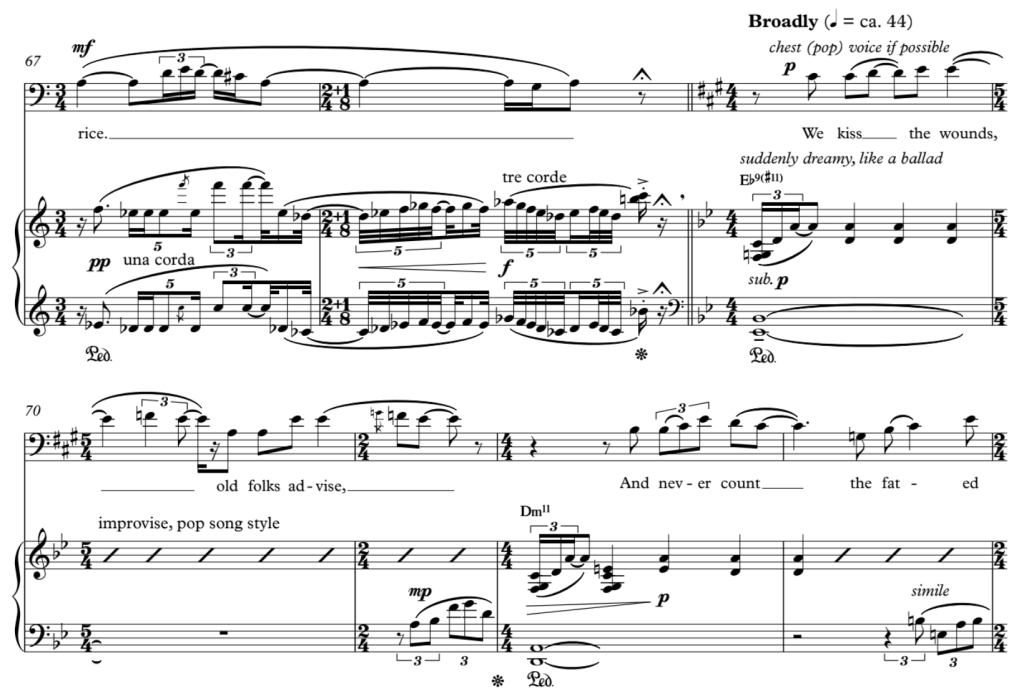

In with fevered dreaming, Badingham writes: “We take what’s given, nothing more // We bury fear, we will be wise.” The piano conjures the sound of bells, similar to the first art song land of the mourning. But the strange festive vibe undermines the gravity of the narrator’s disempowerment, sounding a contrast like a nostalgia out of one’s vivid hallucinations. The narrator speaks not only with inherited learned helplessness but also with an acquired submissive mindset: “Maybe when we treat white people (the “masters”) nicely, they will reciprocate. Then I would be spared from the oppressions I see around me.” I have my share of seeing Filipino hospitality work in full submission for (usually white) foreigners in the Philippines, wondering later how we don’t get the same treatment when abroad.

Should we emulate gratitude, as some Filipinx Canadians admonish, in return for being granted permanent residency or citizenship? Should we force anyone to earn the right for acceptance in a society that views them as inferior? I argue a negative. We were granted admission at the whims of some government’s fallible policy-making. We arrived here under neoliberal systems and global narratives that cajole us to seek greener pastures because ours have turned stale and lacklustre. We don’t owe our gratitude to a fallible sleight of hand, one who stole lands from their original inhabitants. When a people is forced into extermination — whether from death by mass starvation or gas chambers, or from relocation at reserves or concentration camps — its perpetrators lose credibility to assert their legitimacy and morality. Canada isn’t the only one under scrutiny. We simply look at presently occupied Palestine to see the once-oppressed turn into colonial oppressors.

There is no reconciliation ahead.

The delirium takes a postclassical turn. A pop ballad suddenly emerges. A fork on the road. The narrator takes the obvious route, staying put within their nice little world. The piano takes a separate one. Bitonality occurs, as two musical entities suddenly inhabit two different musical keys at the same time. The narrator sings in A major, while the piano conjures a key in B-flat major starting on the subdominant E-flat. The resulting landscape rests on neither side of the coin, continually oscillating as both musicians stick within their chosen paths. The notated score’s two fighting key signatures ensure that they do so.

“We kiss the wounds, old folks advise // And never count the fated score.” The trauma is generational. Here’s a Band-aid and suck it up, says the older one. Of course, they had no recourse back then. Our ancestors dealt with it over and over when Spanish violence, American subjugation, and Japanese invasion slashed through our collective psyche. The elders of today’s diasporas have endured the ignorance and antagonisms of past whiteness to pave the way for our futures. “Don’t keep score of things” — my mother would say during a sibling fight or arguments with her. But keeping score is the antidote to helplessness, the impulse that overthrows dictators, the record that keeps histories reliable teachers of justice. Sometimes I think that Filipinos have largely forgotten how it is to feel a deep collective rage.

with fevered dreaming flings the mezzo-soprano and baritone into a high-pitched pinnacle of forced dramaturgical restraint. Danlie Acebeque performs this art song and comments later in a Vancouver Opera podcast episode: “It’s like literally written for a tenor.” (For the record, I’m a tenor). The feeling of “ngitngit” returns at maximum value, testing the forbearance of a delirious narrator who feels the need to keep the status quo undisturbed. But restraint isn’t resolution nor reprieve. It’s a defense mechanism. I find profound sadness in such a scene.

“That’s a very strong yell. You were screaming.”

My conversation with Carolyn Fe extends beyond her experience of bullying in school. That is for the Living Letter in Liham. She reminds me of our recent gig — I appeared onstage as a collaborative pianist in March 2025 for her musical show Grave Songs, co-presented by Eldritch Theatre. Singer and pedagogue Louisa Burgess-Corbett joined us in our horror-inspired one-hour melange of Broadway selections, Carolyn’s original songs, and classical piano. Within months, I had to pick up a Brahms piano sonata movement and Francisco Santiago’s Nocturne in E-flat minor (1922) in time for the shows.

Carolyn’s husband Luc watched the video and couldn’t continue halfway. “He stopped watching after the Santiago piece,” she tells me. “He stopped there and sighed, ‘I feel the anger.’” It turned out that the curation’s message flew over my head. Starting with a raging Brahms sonata fell into the audience’s expectations. But punctuating a Broadway- and pop-filled program in the middle with an unknown Filipino classical piece? The audience has no escape! Like it or not, they have to sit through and listen to a Filipino voice now. Carolyn continues: “Luc still can’t go past it. He says, ‘I’m afraid what’s gonna happen.’” (Funny then that he hasn’t seen Carolyn’s horrific screaming in Creep [Radiohead] at the end).

I suddenly see two sides of the coin. with fevered dreaming harbours painful restraint, while Grave Songs carries no shame in screaming, “Listen to me!” It’s the duplicity that Said found as a Western literature scholar who begrudgingly thrust himself into international politics. Said noted that a 1969 interview with (former Israeli prime minister) Golda Meir — “There was no such thing as Palestinians” — brought him and others into a massive apology of Palestinian identity and loss. Pushing for the Palestinian cause in American soil also conjured an Otherness. Visiting his abode, a psychologist looked at his piano with skepticism (“Ah, you actually play the piano,” she said) and said she simply wanted to see how he lived before leaving. A publisher refused to sign a contract without a lunch meeting, merely to see how he handled himself at the table. It’s this dance between restraint and yelling that racialized peoples live out amid the staring faces of oppression. Never reconciling.

Fortunes have taught us to abhor this glacial paradise.

A polar vortex casts its freezing spell over the land again; a feverish dreamscape of tropical home ends. Badingham’s libretto ends on that reflection, making a turn back to homesickness. The child of poverty — Anak Dalita — makes a final appearance, still wearing the mask of a major key. The duck walking returns, now oscillating between A-flat major and D major. The clashing key signatures linger on with no resolution in sight.

The lamento structure of Liham demands a descent down to a cadential note at every end of an art song. But in with fevered dreaming, the shifting harmonic colour and the “duck walk” motif deceive the listener instead into an ironic illuminating ascent. It’s the narrator, finally holding their head up high, walking in lockstep with their own truth of homesickness. The deep waters stand still, now frozen as winter moves on. Unmoved.

But truth surpasses resilience. Resilience is a mere excuse to absolve the crooked of accountability. We strive instead to speak our truths, even when voices fall on frozen ears.

If you haven’t visited “Liham: A Digital Song Cycle” yet, I invite you to do so now: https://www.lihamproject.com.

See you in the final essay!

Juro Kim Feliz