Marching child of the sun revolting

Juro Kim Feliz

(part 3 of 5)

N.B. This is the third of a series of five essays around the release of Liham: A Digital Song Cycle. Listen to the art song child of the sun revolting here: https://www.lihamproject.com/child-of-the-sun-revolting

Dear Reader,

Processions are either fun or silent.

I joined our local Santacruzan once during Flores de Mayo as a kid. I never understood why. I wasn’t even raised Catholic. The Santacruzan procession concludes the month-long flower festival (Flores de Mayo) that honours the Virgin Mary during May. But all I remember is my grade school self on a barong tagalog – as any boy escort would wear on formal occasions – walking along our subdivision streets in an evening ritual of pageantry. People joined the march with lit-up candles, holding up colourful and ornately decorated wooden arches to adorn the large entourage in procession. Another vivid memory plays out: I repeatedly called out to my mom at the front and mistakenly hugged a lady stranger who humoured me and laughed: “O bakit, anak?” (Why, my child?).

Biblical characters and queens form this ritualized outdoor spectacle. Apart from Reyna Flores (Queen of Flowers) and Reyna Emperatriz (Queen Empress), the coveted position of Reyna Elena (Queen Helen) makes the front page. Awarded to the most beautiful or important matron, Elena is the star whose identity is not revealed until the very day. The mystery puts intrigue into the Santacruzan that reenacts Queen Helen and her son Constantine’s search for the True Cross. Other queens represent various Marian apparitions, select women characters from biblical stories, and religious symbolisms. They altogether tie a plethora of colonially inherited lore with numerous local ones. This indigenization is a reflection of the islands’ Catholic evangelization during Spanish colonial rule, encouraging the syncretism of pagan lore and Christian doctrine as a strategy to convert the native population. This understanding is all in hindsight, as my child’s mind wouldn’t grasp all that.

Ritualized pageantry doesn’t interest me, but it was different in 2012 when I visited Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Compared to noisy New Year’s Eve celebrations, the Mubeng Beteng (literally “around the fortress”) is a silent procession around the old city walls during Malam Sato Suro – the eve of the Javanese/Islamic lunar year. I remember getting off a Trans Jogja bus at the Tugu Monument to witness the initial rites there. I followed the entourage as they walked down Jalan Malioboro and met the waiting public at the alun-alun (palace open grounds), jumpstarting the two-hour procession on foot. The sultan’s family, palace servants, and a large crowd of people – including curious me – silently walk the streets with flags, fire-lit torches, a suspended gong on a bamboo pole, and heaps of vegetable offerings. Footsteps were silent and introspective. Adherents walk barefoot to feel the earth as they wean themselves off the past year’s burdens and feed off from renewed spiritual energy.

The Mubeng Beteng anchored on the mysticisms of Javanese lore. Interestingly, Susanne Rodemeier (2014) identifies a power struggle between Javanese identity and religious fundamentalism in this practice. Muslim fundamentalists claim such practices as against Arabic Islamic teachings. Mount Merapi’s 2010 eruption and the national government’s earlier demands for a democratically elected sultan/governor in Yogyakarta – a region with special status and jurisdiction – ignited the Mubeng Beteng walks of that time. More than spiritual walks, these processions suddenly stood for political and religious autonomy that comprise Yogyakarta’s brand of Javanese identity. I find it poetic to have a cultural practice take the place of an overt protest, changing ways people choose to participate. Even footsteps in themselves can embody and communicate rich meanings.

Footsteps once marched along trails, now buried in histories.

“Kapwa” (a shared self and identity) allows collective mobilization to take root in Philippine religious practices even under great risk. The annual Feast of the Black Nazarene in Manila draws millions of barefooted devotees – they reenact the transfer of the life-sized Jesus Christ statue from Manila’s walled section of Intramuros to its current abode at Quiapo Church. (Aside from its confirmed presence in the Philippines in 1650, there are no known historical records that show the image’s arrival in Manila nor the date of its transfer to Quiapo Church). Multitudes parade the image out on city streets for extremely long hours, struggling for opportunities to wipe the image with a cloth for curative powers. These processions have a notorious reputation as they render casualties and even deaths from tropical heat exhaustion or being trampled by crowds.

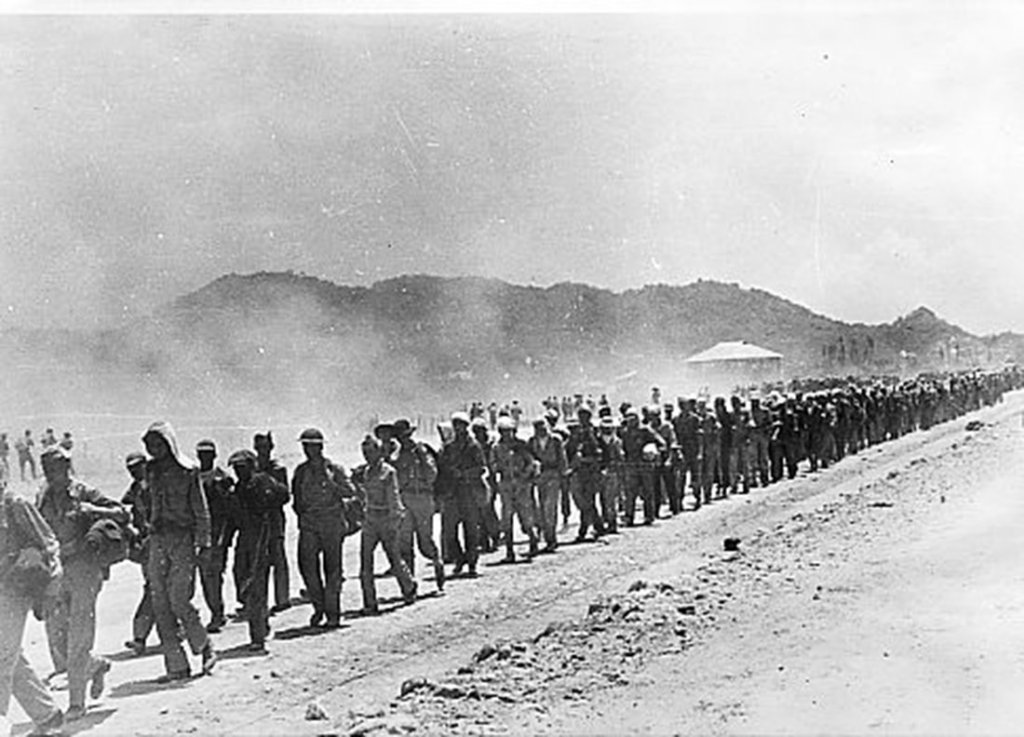

Let me step away from religion. The imperial Japanese invasion during World War II caused widespread destruction and death to the Philippines – under American occupation at that time. Philippine and American forces put up defenses on multiple fronts, with one of the last stands during the Battle of Bataan [“ba-ta-án”] in 1942 off a peninsula opposite Manila across the bay. American surrender rendered victory for the Japanese army, who rounded up around 76,000 Filipino and American defeated soldiers.

Relocating all of them without means of transport led to the Bataan Death March on April 9th of 1942. Japanese soldiers forced prisoners of war to walk 105 kilometres from Mariveles, Bataan to Capas, Tarlac under brutal conditions, intense summer heat, and the captors’ murderous sprees. Around 18,000 died from this ordeal. Japanese generals ultimately paid the price with capital punishment, following Allied victory at the end of World War II and the ensuing court martial trials in Manila. This march is now remembered on both shores – a national holiday (Araw ng Kagitingan) in the Philippines to honour its veterans, and its inclusion in education curricula alongside annual commemorations in some American towns and cities.

Collective selfhood isn’t just confined to military comradeship. The non-violent People Power Revolution is remarkable in toppling down the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos as civilian and military optics saw eye to eye. A million civilians marched toward Metro Manila’s Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) throughout February 22nd to 25th of 1986 in response to defecting military rebels stationed at Camp Crame. Massive nationwide support for the presidency of Corazon Aquino – wife of the assassinated senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Sr. – manifested a long-repressed opposition against the dictator Marcos, who had rigged the national elections weeks prior. Outside Manila, massive demonstrations sprouted as well in Baguio, Los Baños, Cebu, Iloilo, Cagayan de Oro, and Davao.

While military support for the regime crumbled, the church played a huge role in mobilizing the people. Through a Radyo Veritas broadcast, Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin called out for the masses to choose peace for social change. Clergymen, nuns, and religious workers marched out to form part of the frontlines at EDSA, putting moral and ethical pressure on a potentially violent militarized response using military tanks and fighter jets. The strong will of the masses prevailed as they successfully blocked the tanks on the road to Camp Crame. Seeing a lost cause, Marcos, his family, and close allies eventually fled the country. Collective action has its place in ensuring a society’s greater good.

A march sounds out a descent into doom – we should be outraged.

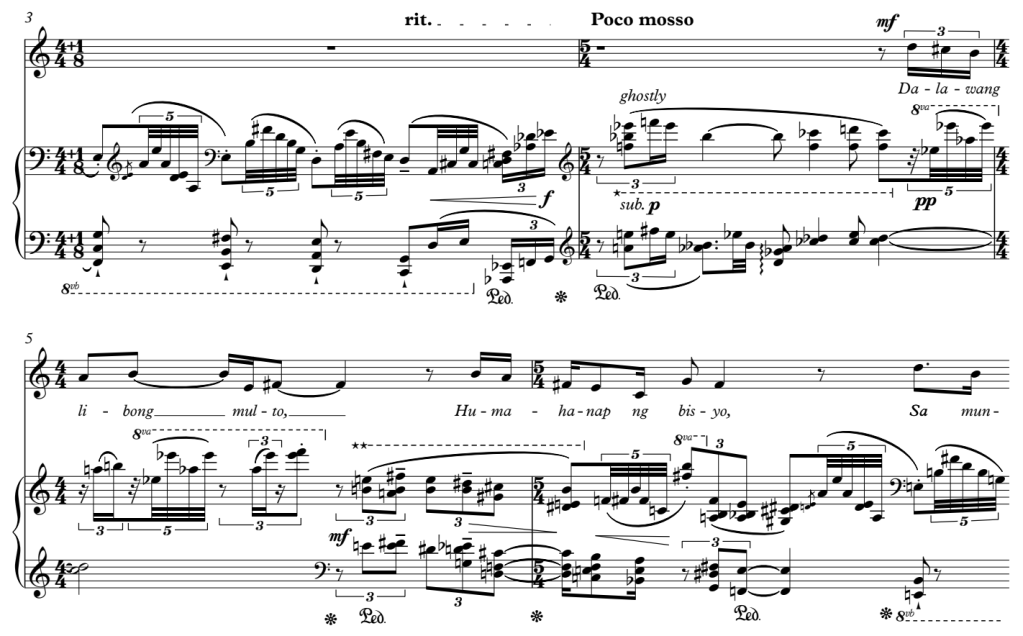

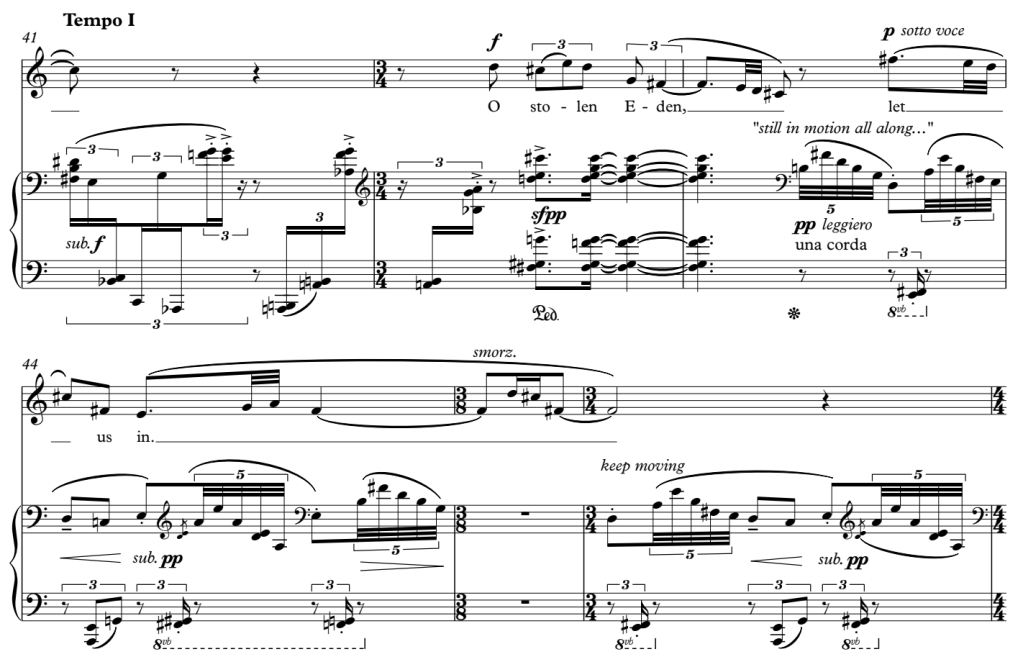

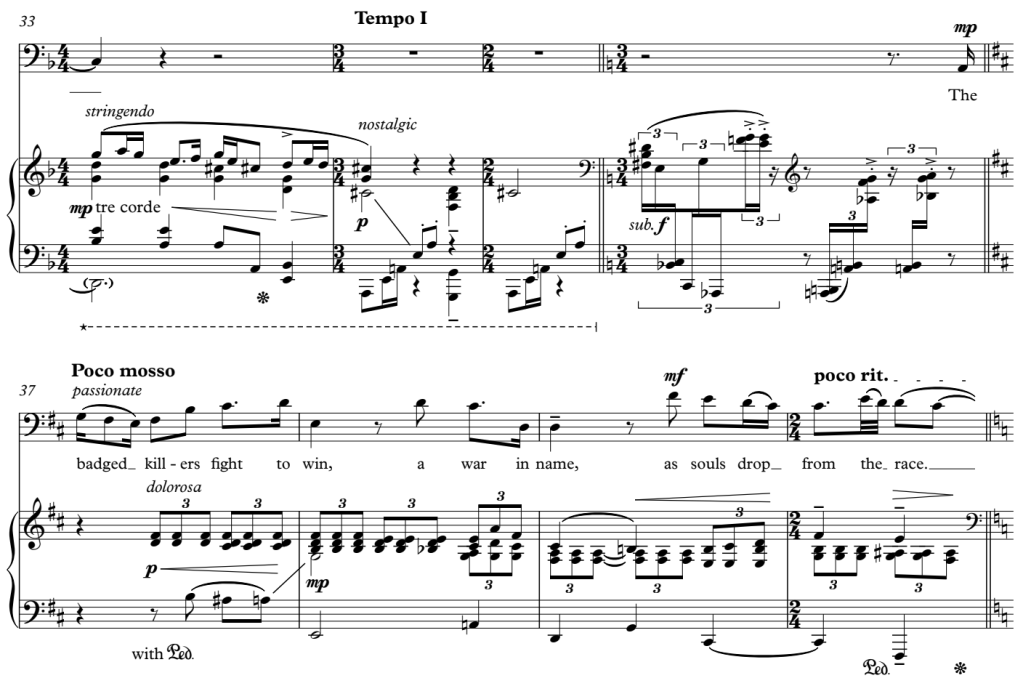

The piano marches forward, its footsteps pounding on pavement with a consistent rhythm. As the second instalment of the song cycle Liham, the art song child of the sun revolting paints a premonition of impending doom. Each step of the way sounds more foreboding and intimidating than the last. The lamento motif that holds all art songs together continues unfolding here – we now stand on its second note “C.” True enough, the piano introduction plays a progression based on a looping descending motif [F-E-D-A], implying a C major tonal space without its blatant pronouncements.

(Read the first essay “Entering the worlds of Liham” to know more about the song cycle’s overarching lamento motif structure).

Revan Badingham III’s libretto starts off with another Tagalog tanaga: “Dalawang libong multo // Humahanap ng bisyo” (Two thousand ghosts // Seeking vices). This a direct reference to the initial death toll from police operations at the onset of Rodrigo Duterte’s 2016 nationwide crackdown on drugs. Citizens, innocent or otherwise, fell victim to the police’s extrajudicial killings as lifeless bodies littered the streets with accompanying cardboard signs saying, “Drug Dealer, Huwag Tularan” (Don’t follow suit). In her memoir How To Stand Up To A Dictator (2022), Maria Ressa remembers her fears of this new campaign that began “turning Manila into a real-world Gotham City, without a caped crusader.”

Slaying innocent youths and planting fabricated evidence outraged the public, with the murders of Kian de los Santos, Carl Arnaiz, and Reynaldo de Guzman in August 2017 being the most notable. Witnesses heard the 17-year-old De los Santos’ last words before his slaying: “Tama na po, may exam pa ako bukas” (Please stop, I still have an exam tomorrow). Badingham’s libretto echoes this in child of the sun revolting – “‘Please stop!’ he begged as lights went dim.” This damning legacy bites back as the International Criminal Court orders Duterte’s arrest for crimes against humanity, successfully subjecting him under custody at The Hague in March 2025 when no one expected it.

The tanaga continues: “Sa mundong kinilala // Ang paala’y nawala” (In a world once known // Farewells have vanished). The injustice of denying one’s farewell didn’t start with Duterte’s hand. The Marcos regime’s crimes include hundreds of “desaparecidos” who mysteriously vanished without a trace. Primitivo Mijares was among them: a veteran journalist and Marcos’ own hand in the press. Mijares defected and fled to the United States in 1975 as he published his memoir The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos (1976). His account exposed the corrupt intent of a long-planned totalitarian rule that eventually led to his sudden disappearance in 1977 and the torture-slaying of his son Luis Manuel (“Boyet”). The ensuing decade of horrors, now known in the present day, were yet to unfold in its full repulsiveness.

Our paradise has been stolen!

Badingham’s libretto makes a recurring motif out of a “stolen Eden” that people clamour desperately for refuge. The prevailing impunity and corruption of governments hamper every passage towards a just society. Pounding incessantly throughout child of the sun revolting, the piano’s marching motif rings out this sinister tone. Exhaustion turns into numbness, making a reprieve from any injustice feel foreign and disconcerting. People in power have always been conniving, so why trust them?

And yet a kundiman sounds out, distorted and yet recognizable, to make way for Badingham’s introductory tanaga. A magical lost kingdom waits to be found. A narrator tells this tale: “Dati akong paraluman // Sa kaharian ng pag-ibig” (I was once a muse // In the kingdom of love). With lyrics by Deogracias Rosario, Nicanor Abelardo’s kundiman Mutya ng Pasig (1926) pulls out a nostalgic metanarrative that the song’s poet retells to anyone who listens. It’s the story of the Pasig River, the muse whose image and song stirs the soul whenever the moon comes out at night. Flowing from Laguna de Bay (“lake of Ba-ï,” not to be confused with the English word “bay”), she adorns Manila of her waters and lays herself freely towards Manila Bay.

Seeing old films like Manila, Queen of the Pacific (1938, directed by André de la Varre) reveal a lot about Abelardo’s Old Manila – a thriving global, colonial city rich with history and commerce, one that the befuddled Pasig River once contended with. The muse further sings: “Ang pag-ibig nang mamatay / Naglaho rin ang kaharian” (When love perished // This kingdom also vanished). The irreparable damage of Manila’s liberation during World War II now overshadows its former glory. Likewise, the kundiman’s ghostly apparitions emerge in the piano soundscape of child of the sun revolting, distracting us from the marching motif at times.

Sanctuaries have long gone – where else can we go?

Let me detract a bit. Denis Murphy and Ted Anana (2004) note that the Pasig River’s deterioration and decreasing fish migration from the lake were already noticeable in the 1930s. (Abelardo and Rosario died in 1934 and 1936, respectively). Manila’s increased urbanization and ferry transport along the river ushered in more industrialization, polluting the river so much that it was declared biologically dead in the 1990s. Rehabilitation programs are now in place to great effect, but they are also fraught with social problems including forced evictions of informal settlers along the river that point to the complexities of urban poverty.

While the glorious days of pre-war Old Manila are long gone, we don’t ignore “Empire” and its lingering remnants. Western modernity arrived in the archipelago at the expense not only of indigenous lore and identity – with centuries of Spanish-American colonial ownership and erasure – but also of ecosystems and natural habitats. Exacerbated by the devastation of World War II, Manila’s imperial position brought excessive migration to the capital. Informal settlers without social safety nets started occupying urban spaces, leading to “squatter communities” living in intense poverty and subhuman conditions throughout the next decades. Resource extraction of foreign companies forced further massive displacement of peoples from ancestral lands as deforestation and mining benefited foreign shores.

Today’s globalized neoliberal economies feed on cheap labour in poorer countries, making production profitable for the Global North while limiting standards of living elsewhere. Unsurprisingly, people fleeing poverty now look to the richer Global North for sanctuary, much to the Northerner’s disdain. Hence, our migrations. With brain drain, the capacity to metaphorically build sanctuaries for the people grow weaker and weaker.

It’s my second day in town and I’m already out to do fieldwork.

Getting off Burnaby’s Royal Oak Station, I look up the address of my destination. “This looks like an industrial part of town,” I ponder as I walk eastward along Imperial Street. There are many auto servicing shops around – how do I find the right one? I stop in front of Pro-Tech Auto Repair while figuring out a phone app feature that’s not working. As if on cue, Renee Fajardo comes outside to greet me. I voice out a complaint: “My recorder app’s transcription feature isn’t working, right when we’re about to interview someone.”

Nigel Elivera doesn’t appear outgoing. And yet he starts telling stories without hesitation as I turn on my Zoom recorder. He was born in Canada to Filipino immigrants from Dumaguete and Davao City. One thing is clear: the family sought to live out the so-called “Canadian dream.” Other relatives also left the Philippines to seek out opportunities elsewhere. Elivera tells us: “We have aunts in Italy, in Thailand, in Saudi Arabia. It’s been in the family that it’s a norm at this point.” Canada is the land of opportunity that brought his mother and father – a seaman-turned mechanic – to own a shop and forge an entrepreneurial road ahead. Elivera followed this path, now being the owner of Pro-Tech Auto Repair in Metro Vancouver’s suburb of Burnaby.

Amid leaving home, the Filipinx diaspora inherits an unshakeable pride. In his Living Letter, Elivera speaks of Filipino pride, the flag that shines through the land of opportunity. Here, I recall the first measures of Nicanor Abelardo’s Bituing Marikit (1926) – the music begins too poignantly that it ironically transfigures a troubled romantic passion into one of lightheartedness. It’s a “danza menor,” one Abelardo wrote for theatre actress Atang de la Rama in his sarswela Dakilang Punglo, with libretto by Servando de los Angeles. Bituing Marikit likens the beloved to a beautiful star amid all woes in life. The narrator anticipates the joys of love in the song’s inevitable major key shift: “Lapitan mo ako, halina bituin // Ating pag-isahin ang mga damdamin” (Come near me, my star // Let us unite our passions). While anti-colonial undertones resound a love of the motherland and her freedom, it rings differently for those seeking freedom elsewhere.

Freedom of movement is a universal human right – but not if it’s inconvenient.

Brits and Europeans arrived in droves at the newly-established dominion of Canada during the 1880s. But historical records of earlier arrivals from Asia also exist. David Lai (2003) notes Captain John Meares’ memoir that recounts shipping Chinese labourers to Nootka Sound, BC in 1788 to build a fort with their assistance. Joseph Lopez (2021) excavates the once-lost history of William “Benson” Flores, Canada’s first known Filipino settler who came to Bowen Island, BC in 1861.

Migrant workers arrived during the gold rush of the 1850s and the construction of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s. But favouring European migrations, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 imposed a hefty $50 head tax for Chinese immigrants. This tax later increased multiple times up to a whopping $500 per person in a series of laws passed in British Columbia and Newfoundland. The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1923 eventually prohibited the entry of migrants with Chinese heritage. After exploiting Chinese labour for the railway’s construction, this racist restriction reflects the worst of Canada’s immigration history.

Badingham’s libretto for child of the sun revolting echoes again: “O stolen Eden, let us in.” Exclusionary policies were repealed as Canada joined the United Nations in 1947 and espoused its Universal Declaration of Human Rights – including the freedom of movement. Immigration legislation in 1952, 1976, and other regulations implemented in between rectified such discriminations. Even when earlier Filipino communities settled in Winnipeg during the 1930s, later changes only fully welcomed people like Elivera’s parents with open arms.

Charles Simic writes: “It’s hard for people who have never experienced it to truly grasp what it means…”

If only borders would let everyone in without hesitation. And yet a nation-state’s borders keep national and economic security intact. With global inequality in place, it’s in the rich countries’ best interest to keep the reins in as much as possible. Lest vast resources – historically exploited from Europe’s enslaved and colonized – end up in unwanted places, landing on the wrong hands. Lest rich countries lose their power and privileged ways of life, as they see the greater poor of the world take over to reclaim their dignity back.

In Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss (1999, ed. André Aciman), Charles Simic talks about the conundrum of lacking proper documents in a foreign country as a displaced refugee in 1945. His family fled Belgrade during World War II to avoid indiscriminate airstrikes. Finding themselves in Paris, this refugee’s ordeal of getting residency permits from the Préfecture de Police during the age of postal mail was all too resonant for me. (Connected to the French interior government, the Préfecture is responsible for issuing ID cards and permits to residents). Simic’s cynicism is blatantly evident: “…if the weather was nice, we’d go and sit outside on a bench and watch the lucky Parisians stroll by…while we cursed the French and our rotten luck.”

But child of the sun revolting takes a homeland’s point of view. We go back to the violence and impunity of Duterte’s so-called “drug war” in the Philippines. For many people, there is nowhere else to run and escape. Worse yet, fellow countrymen also stand as the oppressors. The absurdity of it all rolls out like a comic tragedy – even the colonial injustices and atrocities of semi-fictional Spanish characters in Jose Rizal’s novel Noli Me Tangere (1887) appear way too larger than life. Amid the rage and drama, Rizal wanted us to laugh at how all these circumstances look so ridiculous. “Woe is me,” we laugh out of helplessness. The recent global trade wars and immigration-related foul play that the United States spins show us their utter foolishness in full view.

“There is lots of screaming.”

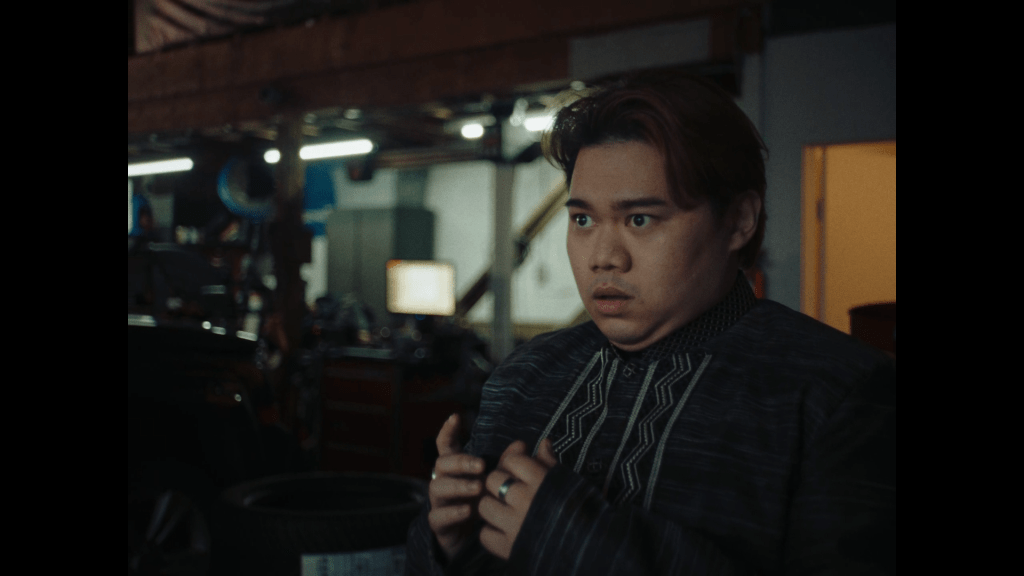

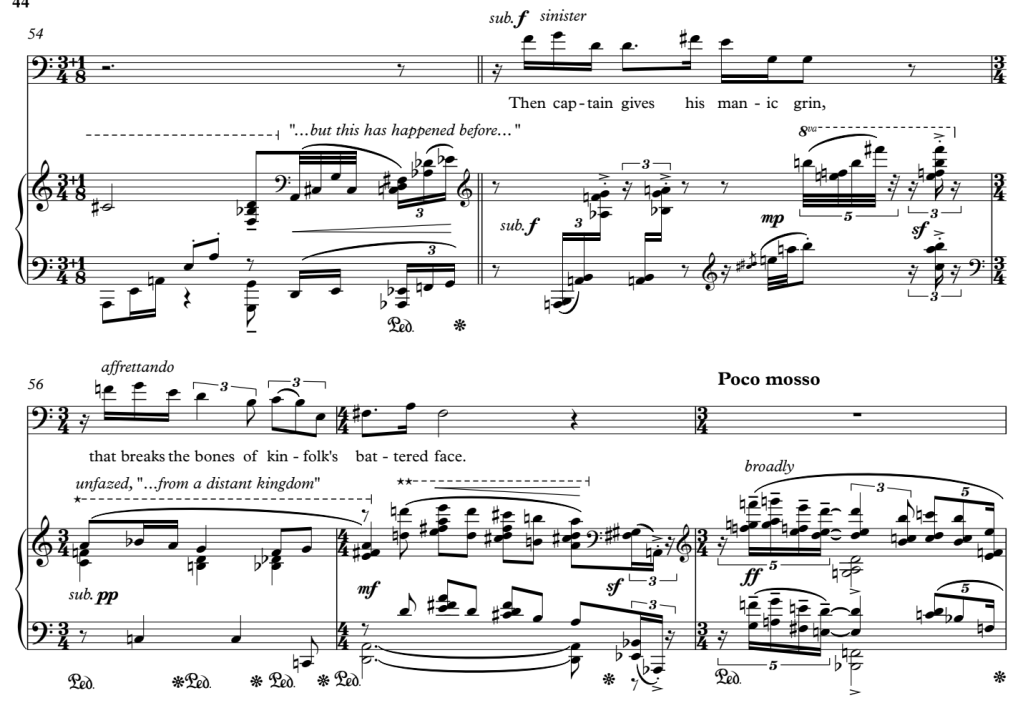

Danlie Acebuque comments on the art song in a Vancouver Opera podcast episode in June 2025. child of the sun revolting is littered with high notes and drastic leaps. The range is somewhat extreme for a high baritone, much less so for a mezzo-soprano. But Badingham’s libretto demands it: “They wail at sirens, mad as sin.” A villanelle prescribes formulaic sequencing of recurring poetry lines; a certain rhythm emerges in the images it invokes. The narrator recounts the horrifying assaults of those in “blue and red” – the badged killers, the so-called “gods of steel and grace” whose captain carries a manic grin. They do as they please without dire consequences. The common folk fall victims to this social cancer while calling hopelessly for sanctuary. The villanelle structure makes sure that these images oscillate back and forth, telling us that there’s no way out.

But serving as counterpoint to the sung texts, the music is frantic, satirical, even comical – not because it’s funny but because it’s ridiculous. The piano can’t sit still within a coherent landscape! One aggressive gesture illogically follows a kundiman quotation and shifts back to the marching motif, then gyrates back again. The blue and red’s assaults come with mysterious piano grooving (in A minor!), Stravinsky-esque “The Rite of Spring” blathering, and naughty danza rhythm flirting from Bituing Marikit. The narrator sings: “The badged killers fight to win // A war in name, as souls drop from the race.” Out of nowhere, the piano responds with an overly contrived melodramatic music in B minor that sticks out like a sore thumb. “[Breaking] the bones of kinfolk’s battered face” sounds out a mocking Mutya ng Pasig melody that sings, “Dati akong paraluman” (I was once a beautiful muse). The only constant here is this return to the death march, playing in the background as if someone fell asleep and left their television on.

You can blame Erik Satie for this shindig. I performed his piano piece Embryons desséchés (1913) a couple of times in the past and always laughed at its foolishness. Satie’s comical use of text descriptions in the score are never prescriptive nor helpful. He would label a passage “comme un rossignol qui aurait mal aux dents” (like a nightingale with a toothache) that has a mischievous four-note motif traveling down the piano in six octaves! Another passage is a “citation de la célèbre mazurka de Schubert” (quotation from a celebrated Schubert mazurka) where “ils se mettent tous à pleurer” (they all start crying) – except that Schubert never wrote a mazurka! Satie makes fun of Chopin’s “Funeral March” here (from Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor). But the most hilarious thing about it? Everything is concealed from the audience. They only listen during a performance and never see the score. In Dadaist fashion, it’s all a running gag between you, the performer, and Satie, the composer.

“It ends the day the people scream” – can we still revive the dead?

There’s another kundiman that I still haven’t mentioned. With lyrics by Jose Corazon de Jesus, Francisco Santiago’s Madaling Araw (1946) passionately beckons a lover closer to revive them from dying of misery: “Kung ako’y mamamatay sa lungkot niaring buhay // Lumapit ka lang, lumapit ka lang at mabubuhay” (If I end up dying in this life’s misery // Just come near and I will be revived). If you’ve followed along, the kundiman’s formulaic minor-major transition is an idée fixe at this point. Sure enough, the modulation to a major key in Madaling Araw signifies revival and renewal. Like the dilemma encountered in the first art song, child of the sun revolting cuts out this particular modulation and renders it non-functional as a result. The quotation is another ghost that roams the landscape alongside those who were killed mercilessly without reason.

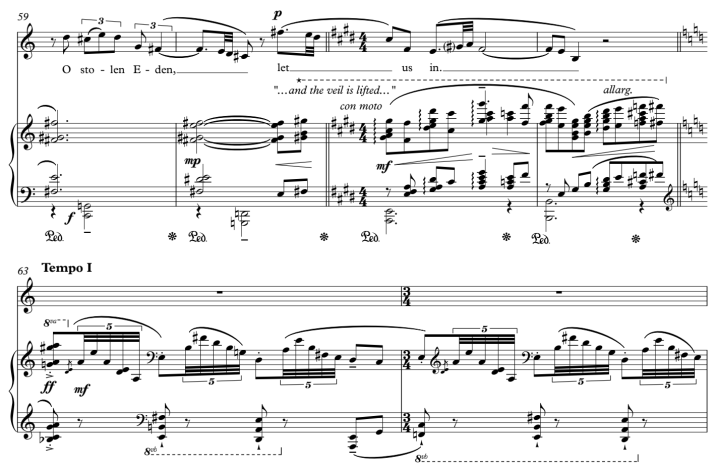

The narrator of child of the sun revolting calls out again: “O stolen Eden // Let us in.” Mutya ng Pasig suddenly comes out in full bloom, its melody taken from lines that similarly speak of revival. “Kung nais ninyong ako’y mabuhay // Pag-ibig ko’y inyong ibigay” (If you want me to live on // Offer my love to all). Unlike other ghostly encounters, this is no longer an apparition – it’s the Pasig River herself in a climactic exposition. The veil is lifted, and she shows her true form to the listener. The dying muse pleads for a direct call to action: Give my love to all.

With a tumultuous childhood in war-torn Europe, Charles Simic is terrified and critical of collective ideologies and their euphorias. He claims: “The executioners’ best friends have often turned out to be writers and intellectuals.” The intellectual projects of fascism and communism hold innocent bystanders with disdain. Simic says that the innocents are swept aside and easily discarded because they are in the way. And yet, if he could only see the world now. The slaughter of innocents he feared happens right now because naïvety and apathy are the exact culprits that conjure demons out of their hiding places. It’s the same passive bystander who propped up authoritarian figures, the “trapo” (traditional politicians), the political jesters who aren’t even entertaining at all. The murderers.

The piano’s satirical death machine now appears to lose momentum. It lands on a B – its resting point. The narrator barely utters their last words, still begging for sanctuary. If only Filipinos would take heed, start throwing the beasts out in vindictive rage, and clamour for justice. “Kapwa” should revive our senses, taking our gaze away from corrupt selfishness. We should look out for others and build our own Eden gardens. Most importantly, we should let others in. Oh, how I’ve seen many who build their finely curated gardens – their communities, their cliques, their “bros” – only for their own sakes!

I look back at our interview with Elivera: “I want to be part of that dream to be someone successful, to be someone who can help out in the community. That’s where I feel like I started from.”

Here is a child of the sun, thriving. We should aim to thrive. In the eyes of our oppressors, thriving is revolting.

If you haven’t visited “Liham: A Digital Song Cycle” yet, I invite you to do so now: https://www.lihamproject.com.

See you in the next essay!

Sincerely yours,

Juro Kim Feliz