Mapping the land of the mourning

Juro Kim Feliz

(part 2 of 5)

N.B. This is the second of a series of five essays around the release of Liham: A Digital Song Cycle. Listen to the art song land of the mourning here: https://www.lihamproject.com/land-of-the-mourning

Dear Reader,

“I’m interviewing someone and I’m running late!”

The titillating soundscape of commuters exiting North Vancouver’s Lonsdale Quay terminal caught my attention the first time. With a musical project in mind, I returned days later and rode the ferry across the bay to capture field recordings of multiple turnstiles beeping off relentlessly. I should have gone earlier – wriggling out of North Vancouver back to the mainland during rush hour was a bad idea. Finishing my task, I crossed the channel back to Waterfront Station and muttered silently once I got inside a crowded SkyTrain. For someone holding an interview soon, I was already out of breath.

I’m accustomed to urban life in Canada within my twelve years of residing here. Time is linear and plottable like rigid coordinates on the Cartesian plane. I check bus schedules whenever I leave the house because they are predictably plotted out. Any second wasted from mindless delay and I would entirely miss my ride. My life orbits around gravitational forces: teaching schedules, appointments, calendar entries. Habits are predetermined based on specific times of the year: from winter chills and summer heat to tax seasons, grant applications, and commissioned projects. The clock is the bulwark of Global North productivity, a machine that never stops.

Attitudes around time vastly differ in the Philippines as I remember it. Time is a river where water flows endlessly. The sun and moon rise and set in an endless cycle. The monsoon season interrupts hot summer months without clear-cut precision, predictability, or inevitability. A jeepney or bus would eventually pass by the road, their frequency depending on which drivers decide to show up at the times they do. Conditions of poverty make the clock a needless fixture outside school and work productivity. Tardiness feels inconsequential amid a culture that sways on the ebb and flow of infinite time, like bamboo swaying in strong winds. Locals have a common joke: mabuti pa yung mga hindi pinaplano, natutuloy [unplanned activities happen more than those we schedule]. The tambay (derived from “standby;” one who sits around, doing nothing) lives on.

I arrived fifteen minutes late, thankfully without consequence.

Plato Filipino Restaurant sat at the heart of Vancouver’s Joyce-Collingwood neighbourhood, a stone’s throw away from the SkyTrain station. The warm colour palette of its open space interior reminded me of canteens and carinderias you would find in the Philippines. I found Renee Fajardo talking to Bennet Miemban-Ganata, owner of the restaurant who I lost no time with in introducing myself. I turned on my recorder, and the ensuing two-hour conversation with her now lives on as a Living Letter in the Liham website.

Miemban-Ganata’s Living Letter told an amusing story of her daughters who try their hardest to speak Filipino that they never really learned growing up. They blamed their parents for not teaching them the language. I remembered laughing loudly as she reenacted their attempts: “Mom, tumahimik ka. Madaldal na.” [Mom, that’s enough. You’re too talkative now]. Not surprisingly, this story only touched the surface of a bigger conversation on younger diasporans who now find themselves reclaiming their roots.

“Yun yung napapansin ko sa younger generation,” she told us. (This is what I notice with the younger generation). Miemban-Ganata referred to the children of friends and in-laws who grew up in North America: “They really find their roots, they have this hunger to learn how to speak Tagalog. It will come to a point na hahanapin nila kung saan sila nanggaling.” (It will come to a point when they will crave to know where they came from). Reclaiming lost time brings profound consequences in how people position themselves within a society that grows more multicultural by the minute. There is a recognizable need for making their lives legible. Those estranged from the homeland are now the most enthusiastic in anchoring themselves, a vindictive act from the pressures of assimilation and losing their identities as a result.

“Ang lahing kayumanggi // Isang araw gaganti” [The brown race, one day it will retaliate].

Revan Badingham III’s libretto for the song cycle Liham sets a defiant mood with the introductory tanaga of the first art song land of the mourning. It stands as a warning not to forget who we are. “Ang bilin ng matanda: huwag kang magpapawala” (The old one’s instruction: ‘Do not lose [yourself]’). Why am I reading a manifesto here? I thought upon first reading. It occurred to me later that expressions of solidarity are gestures of love and horizontal comradeship. Benedict Anderson (1983) touts these sentiments as the ground zero of nationalism.

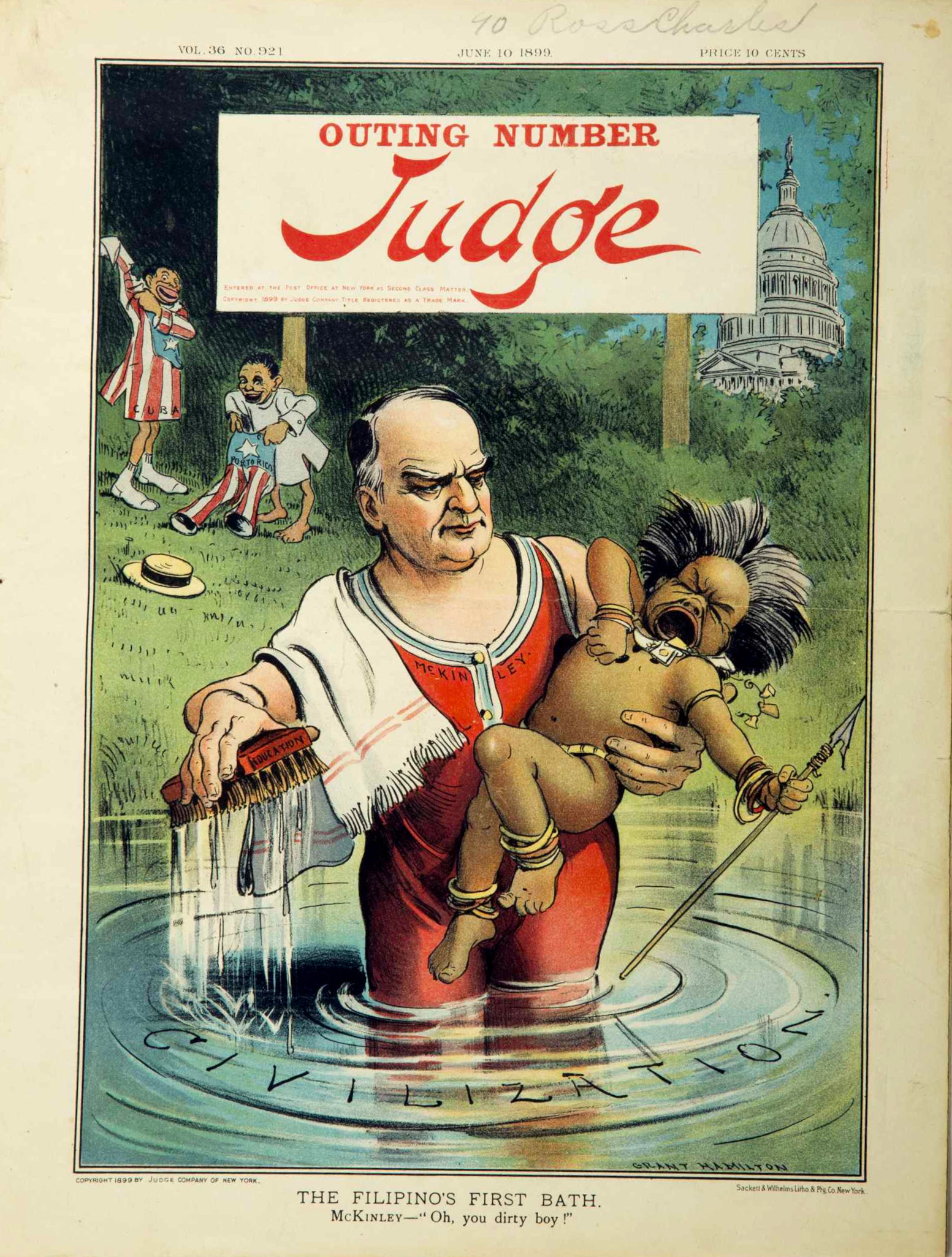

I see reclaiming one’s heritage as resistance to white supremacy. “Whiteness” does not solely refer to skin colour – not making a case against fair-skinned people per se – but stands as an overarching superiority and exceptionalism. Legacies of imperialism and colonial subjugations among European and North American positions birthed these privileged worldviews. It propels how people weaponize everything rooted from skin colour to exercise power. We see that in caricatures of brown/black-skinned Filipinos in American editorial cartoons and propaganda, making a case for white saviour complexes to civilize the so-called “savage.” Rudyard Kipling invoked that in his poem The White Man’s Burden (1899), fueling imperialist desires as the United States annexed the Philippines right after Filipinos revolted en masse against Spain.

Whiteness also refers to absence. It’s the whiteness of an empty canvas where positivist thinking spills out images of progress. A white canvas ensures the illusion of objective reasoning, without messy stains of baggage that taint people’s visions into subjective and divisive directions. The only singular way is forward and up. Of course, who dictates where “forward and up” is? Erasing these pluralistic subjectivities enables a singular power into full control. People spew out claims of Western superiority as the birthplace of the modern world. And yet we see the debilitating negative impacts of its technological advancements and misplaced faith in individualism – with social, geopolitical, and environmental costs.

Even Filipinos need revolutionary paradigm shifts.

Global North assimilations proved strategic for Filipinos to avoid oppressions abroad. Some children born in the diaspora were denied exposure to Philippine languages at home, long believed to facilitate faster English learning without the betrayal of accents. North America’s so-called “neutrality” in accents remains an aspiration – admittedly nothing more than making one’s voice legible to white ears. In the homeland, skin whitening products and popularity of fair-skinned celebrities in mainstream media manifest classist perceptions of brown skin as inferior. Brown-skinned people are the “anak-araw” – sun-baked people of lower classes who make a living out in the sun.

This renewed reclamation is now a paradigm shift, a revolt against the default of whiteness. Making native languages visible is a revolutionary act within a global society that favours dominant European languages. Recorded histories dispel prevailing ideas of void emptiness before the advent of colonization. Our ancestors aren’t devoid of literacy, sophistication, elaborate social systems, and navigational prowess across seas. The tanaga in Badingham’s libretto is proof of living pasts – this indigenous literary form encapsulates proverbial lessons that are traditionally passed orally. I can imagine elders sitting around during feasts, passing on a number of tanaga they know by heart to the younger crowd to teach life lessons.

Uncovering lost pasts also realigns a reclamation of lost futures. Beyond undoing erasures, this consciousness points to a dormant power, left untapped because of the distractions of whiteness. Miemban-Ganata believed in this when she saw limitless possibilities as a former delegate representing the Philippine government in international conferences. She asserted during our conversation at Plato: “We have theatres like the Met…and we weren’t able to maintain them. The government didn’t give them enough attention, not realizing that this could generate income to the country and proper recognition around the world.” Once the home of international artistic productions since 1931, the Manila Metropolitan Theater had its history of closures and restorations following the capital city’s devastation after World War II. A lost chapter now starts anew with the complete restoration of Juan Arellano’s art deco architecture and the discovery of Francesco Riccardo Monti’s original bas-reliefs on the proscenium arch, opening the theatre doors again in 2021.

Where there is revolution, the bells would toll from yonder.

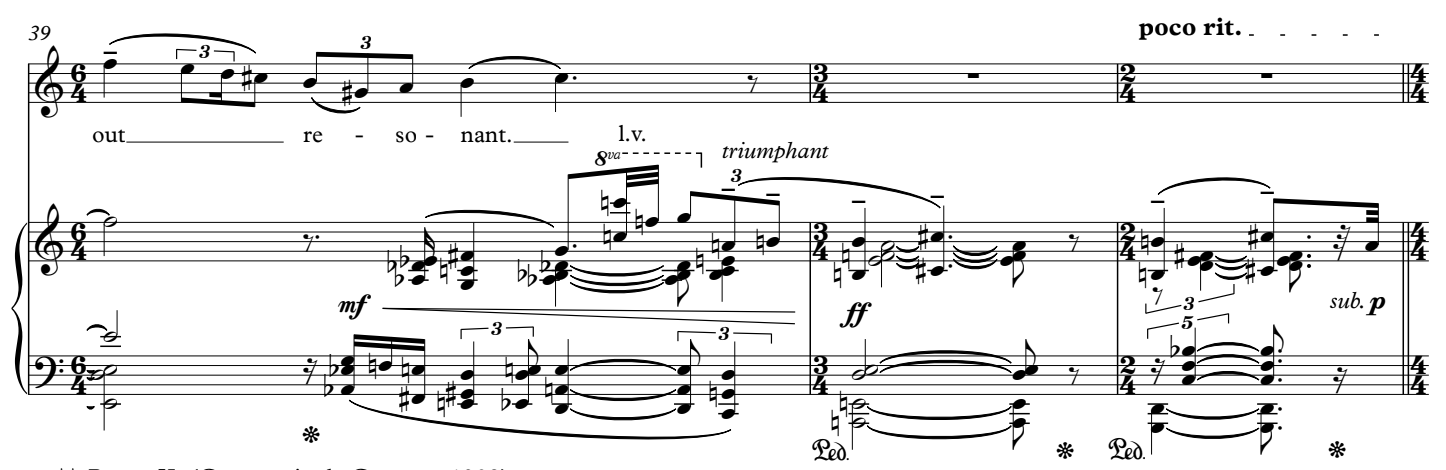

The piano centres its sparkling octavian outbursts on D, initiating resonant calls from seemingly simultaneous tolling bells that create melodic contours. The singer starts its song on a C-sharp, its diatonic landscape rubbing against the piano’s spiky, kinetic surfaces. In land of the mourning, there is no room for hesitation – it is rather urgent to shove, to push forward in time. Battlecries wait for no one.

Splattered bell sounds occasionally invade memories of my college studies in the Philippines. A carillon tower at the University of the Philippines stands beside the main theatre and my college building. The university had decommissioned the deteriorating bells in 1988 and initiated a restoration project that reinstalled 36 new bells twenty years later. Random melodies ringing at five o’ clock in the afternoon would cue the end of a school day as the sunset evoked yearnings now unmasked in the evening city vibe.

Bells have a history of signifying war, battle, death, and mourning. Ominous tolling announces military action, dire warnings, and a sending off for those who died. Bells go first in line for metal smelting when the need for artillery and ammunition arises. Inaugurated in 1952, the University of the Philippines’ carillon tower served as the epicentre of intense activism and mobilization before the dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972. The bells would ring as students sprang into action in protests and picket lines, defending the university as an area free from policing and military meddling during the First Quarter Storm of 1970.

Bells were also symbols of imperialist conquest.

Christianity’s arrival in the Philippines at the onset of the Spanish invasion also meant the invasion of symbols, physical objects, and systems that ultimately changed indigenous lives. The inquisition would bring the practice of bellfounding in the islands – church bells are surely commissioned whenever a church gets newly erected. Casted in 1595 at modern-day San Carlos City, Pangasinan (formerly Binalatongan), the Sancta Maria de Binalatoga bell stands as the oldest in Southeast Asia. It’s striking that only decades have passed since Miguel Lopez de Legaspi established the very first Spanish settlement in Cebu in 1565 and captured the city-state of Maynila (now Manila) in 1571. The Palaris revolts in the 1670s would bring Spanish authorities to burn the town of Binalatongan and relocate the bell almost 300 kilometres away in Camalaniugan, Cagayan, where it now rings.

Centuries later, the Treaty of Paris in 1898 ensured that Spain would sell the Philippines to the United States. The newly-established Filipino revolutionary government that overpowered Spanish rule now faced American invaders, leading to the Philippine-American War in the same year. In 1901, a bloody ambush of the US Army’s 11th Infantry Regiment – set up by the Philippine Republican Army and locals of Balangiga, Samar – led to American retaliation, prompting an order to kill all Filipino civilian men in Samar. The three bells of the Balangiga church were taken as war trophies, as American forces massacred, looted, and recaptured the town. After almost a century of American refusal to relinquish the bells, they were finally repatriated back to Balangiga in 2018 as a symbol of goodwill.

Signals warning the arrival of American troops in Balangiga were attributed to the small bell. And yet, I also find poetry in bell sounds. Maurice Ravel dedicated the piano suite Miroirs (1905) to specific friends who mobilized against the Parisian establishment as artistic modernists. La vallée des cloches runs last in this collection, which he dedicated to the composer and pianist Maurice Delage. Listeners hear a two-note bell motif throughout the music, but I hear Ravel’s chinoiserie dibs yet again in evoking infinities with stratified punctuating layers seen in Javanese gamelan. Imperialist conquest also governed Europe’s orientalisms – keeping “whiteness” centered around everything else – but I find the collusion of bells, metal bars, infinity, and artistic mobilization surprisingly poetic. Sounding bells from a valley might be an afterthought after Ravel and fellow advocates mobilized to support the premiere of Claude Debussy’s opera Pelleas et Melisande (1902) and establish its cult following. The infinity in looping back lost pasts enables time warps to rehash the myths and stories that bind solidarities into a living narrative.

There is a path upon which the singer drags their feet along.

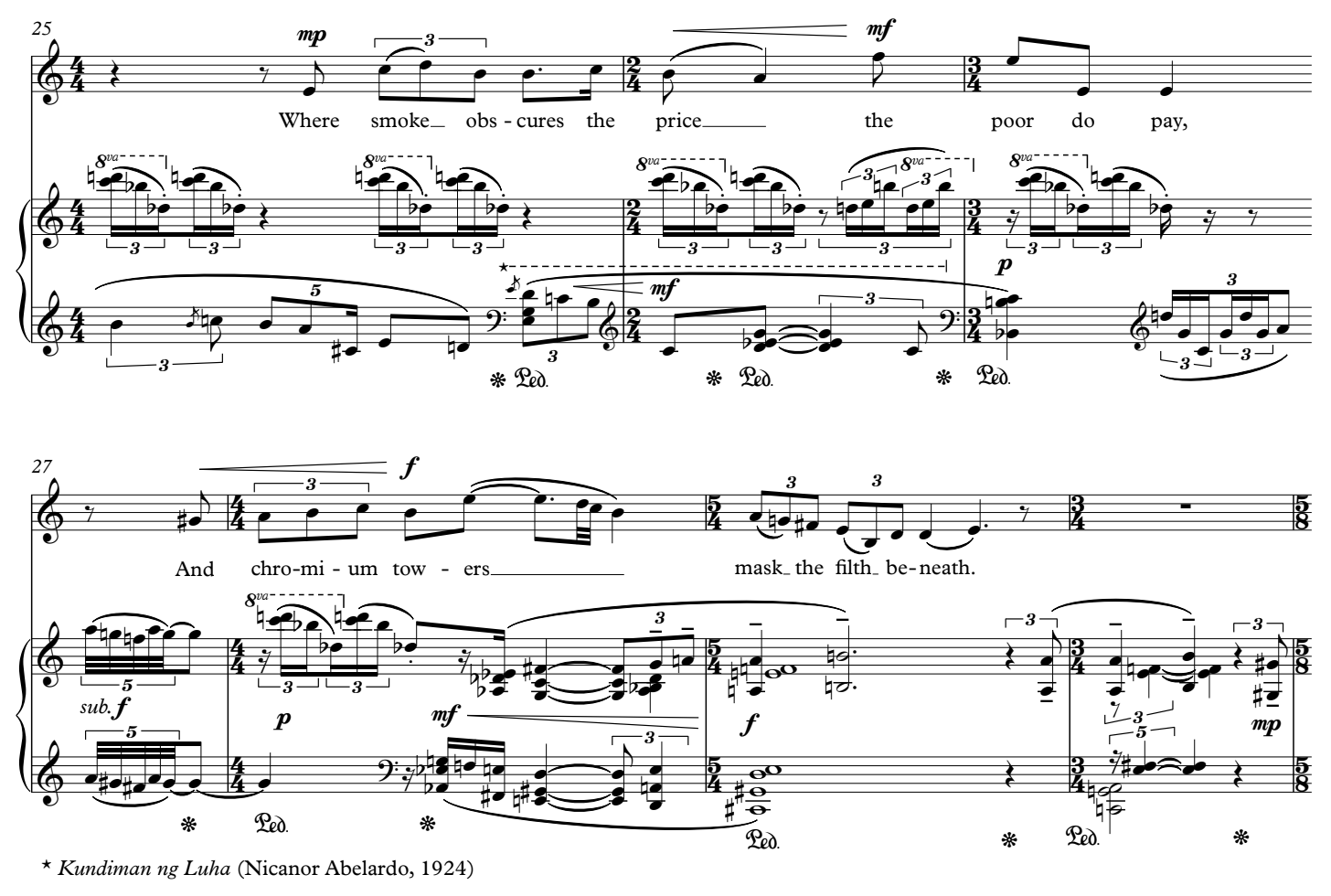

land of the mourning finds affinity in clanging bells as a symbolic call to arms, preceding a landscape that bears traces of Nicanor Abelardo’s Kundiman ng Luha (Song of Tears, 1924) and Constancio de Guzman’s Bayan Ko (My Country, 1929). As noted in the first essay, the kundiman art song’s professions of love bottle up undertones of anti-colonial revolutionary sentiment and protest. Amid a defiant battle cry, interloping soundscapes echo the consummation of one’s love for unfettered freedom. But in land of the mourning, the singer also trudges along this muddy trail to urgently speak out from a distance, sometimes even fighting for space to do so.

Jose Corazon de Jesus’ lyrics in Kundiman ng Luha cries for a beloved’s compassion lest they die from unrequited yearning: “Damhin mo rin ang dibdib kong namamanglaw // Yaring puso sa pagsinta’y mamamatay, mamamatay. Ay!” (Feel my chest that sadly cries // Lest my heart die out of yearning. Ah!). The kundiman’s inevitable transition from a minor to a major key always promises a renewed hope and spirit – de Jesus takes advantage of this musical device to intensify a flirtatious yet melancholic plea for a love that lasts until death: “Ilaglag mo ang panyo mong may pabango // Papahiran ko ang luha ng puso ko … Hanggang sa hukay // Magkasama, ikaw at ako.” (Drop your perfumed handkerchief // So that I can wipe the tears of my heart … Until the grave // We’re bound together, you and I).

And yet, it is Abelardo’s instrumental piano transition instead that land of the mourning evokes – an anachronistic, melodic snippet that never functions the way it was intended. No minor key exists to shift into a major key. The emerging gestures are unfettered ghosts that roam on jagged terrain, mourning for their displacement. The singer has no need to recognize them – they’re too preoccupied with their monologues to stop and get dragged with the currents.

Constancio de Guzman’s Bayan Ko does a name drop. The beloved is no longer a nameless entity. It is the Philippines, the Inang Bayan (Motherland) that people have long cried for freedom from its colonial oppressors. De Jesus (the same lyricist of Kundiman ng Luha) translated Jose Alejandrino’s Nuestra Patria in Tagalog – the original appearing in the sarswela Walang Sugat (Severino Reyes, 1902) – to birth out a kundiman. With the growing nationalist movement since the 1960s, Bayan Ko eventually became popular as a protest song and gained prohibition from public performance during Marcos’ authoritarian regime.

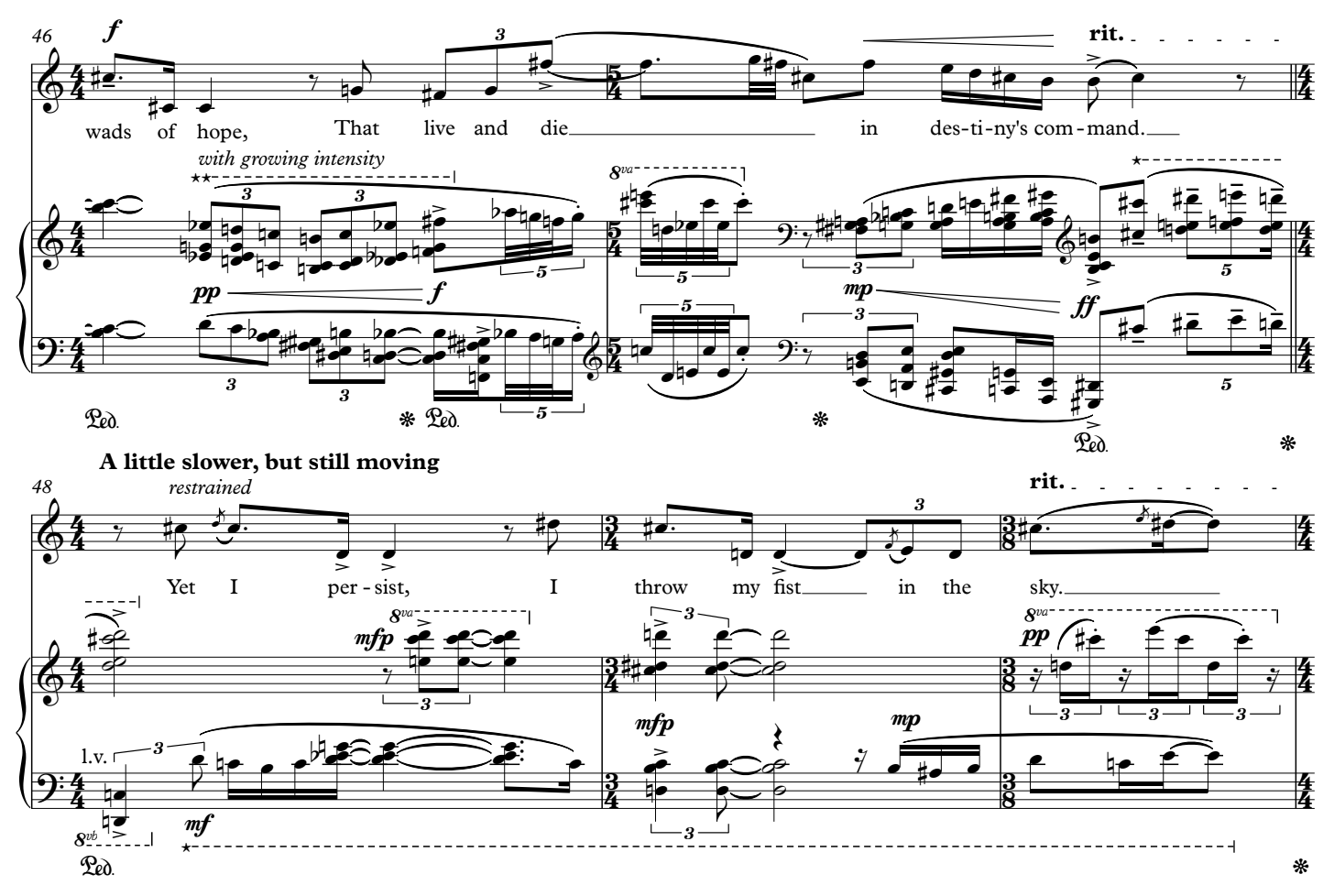

“Ang bayan kong Pilipinas.” (My country, the Philippines). It’s iconic: one only needs to sing the first line for Filipino folks to recognize it. But this patriotic gesture sings out distorted in land of the mourning, appearing before the singer even declares: “The revolution is our battle song.” The irony of playing abruptly docile and diatonic chords in walking rhythms after this outburst plays out a whimsical dramaturgy. What battle songs are we singing again? Is everyone ready to do battle? Or are we falling back to our love of submission, our inability to assert ourselves to keep the peace, our attachments to complacency and mediocrity? There are two speaking voices here: one is passionate and patriotic, while the other one is impish and cynical. You couldn’t tell if “triumph” – the motivic ascent of a whole step interval that punctuates the end of each art song stanza – is of a declarative gesture or a questioning one.

“A land where legends live and heroes breathe.”

On top of the muddy musical trails, Badingham’s Shakespearean sonnet follows the tanaga with powerful declarations of love: “My heart: it lives eight thousand miles away … My soul is seven thousand islands strong … My spirit flies to nine hundred thousand folks.” The embedded iambic pentameter allows a rhythm that renders fluid waters without the trappings of a rigid quadruple structure. The piano takes romantic dives in such poetry lines even with the persistence of bells on top of towering steeples – sometimes invading the senses, sometimes merely hovering.

This time, we hear the bells of the diaspora. I recall my first years of Canadian life in Montreal, where church bells would fill the air every afternoon near my apartment at Verdun. I would also chance upon tolling bells along Place d’Armes – right across the Basilique de Notre Dame – if I hung out at the right time. The sun would then meet the horizon, gradually ushering in the evening aura with the heartfelt songs of a busker at an echoing plaza, stirring both chaos and emptiness deep within the souls of sojourners and drifters. The bells would transport me back to my former school with its carillon tower, city lights, and deep sunset yearnings that harbour a je-ne-sais-quoi. Personal, instantaneous journeys covered tens of thousands of kilometres as my mind would bend space-time. Such travels connive in merging nostalgic pasts with the lonely present while aching desperately for better futures.

The singer of land of the mourning is a diasporan narrator, calling out from a distance. The declarations are strong and clear, and yet they also look inward into self-awareness. Badingham writes of “nine hundred thousand folks who built their homes on frozen stolen land.” There is unceded land – the colonial legacy of an occupying nation-state that both welcomes and evicts. The diasporan is a settler, a guest as much as any citizen of a country whose lands do not belong to them. Our freedom should also require the freedom and justice that indigenous peoples deserve. Are Filipino immigrants aware of this nuance? How would they care if finding a better life is more urgent as their homeland continues to let them down? There is a lot of room for reflection here that the narrator wants us to make space.

Strength is where the convergence lies.

We navigate from Miemban-Ganata’s story in Vancouver toward the sounds of bells, reclamation, war, and diaspora. I finally look back to Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss (1999, ed. André Aciman) to gain more perspective on diasporic place-making. In the essay Shadow Cities, André Aciman fully understood the strength imbued in a map of different geographies to situate his immigrant positionality. For him, New York’s Straus Park is that very fulcrum – the intersection of Broadway and West End Avenue, both West 107th Avenue and West 106th Avenue hugging this small enclave now dedicated to the victims of the sinking Titanic. It is a place that had at least four addresses, giving Aciman fleeting glimpses of London, Amsterdam, Paris, the Italian Riviera, and others out of an imagined older New York that thrived in the past centuries. Shadow cities would pile on top of each other as he would eventually conjure his Egyptian birthplace Alexandria – all within the confines of this small, unassuming park.

I visited this exact spot in 2018, only to lose my phone with my photos of it on that very trip. Nowadays, there are online map repositories to virtually revisit places from a laptop or phone screen. It’s possible to relive one’s past life with Google Maps, all on Street View mode. (I’ve done that!). But technology can be a handicap, dampening vivid imaginations and mental journeys that human minds are capable of. I look at Aciman’s oasis of retrospection, obviously taken from Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities (1972): a fictional Marco Polo tells Kublai Khan of his numerous travels to bizarre cities – from ancient and exotic to futuristic and dystopian. At the end, they turn out to be conjured iterations of Marco Polo’s hometown Venice, seen like a kaleidoscope offering stunning visual transformations of mirrored images.

It hit me. In conjuring this convergence, reclamation comes in full power. Aciman stopped at nostalgic remembering. But we go further and reclaim ourselves to revive our spirits in this convergence. It doesn’t matter if they are shadows of their former selves or preserved living artifacts. Space-time is infinite. No matter how fluid the canvas is, we still try to locate where we are and create a map through triangulations: the bells that call us into action, the songs that remind us of struggles, the languages and memories that pull us to the homeland and out. The English colonial version of the Philippine National Anthem refers to the homeland as this “land of the morning,” the place where the sun rises first. What is there to mourn?

We take the words of this art song’s diasporan narrator again: “My soul is seven thousand islands strong // Our ancestors first travelled continents.” In our displacement, we yearn and mourn the loss of our connections to these islands, to these ancestors. We mourn the loss of predictable futures, only bringing “wads of hope…our only currency” to survive in unfamiliar conditions. We mourn the loss of control and agency, facing our fate that could either bring us to the summit or plunge us into the depths of hell. And yet, seven thousand islands remind us that there is strength in numbers. We live out the collective “we” that crystallized collective memories into living histories. No history book will fully embody this living knowledge.

The melancholia of revolution lies constant, and yet we know we will persist.

The first Filipino manongs (“uncles,” migrant workers) in the American West Coast had already suffered the worst from intense racism during the Great Depression, most striking in Carlos Bulosan’s writings. But now is the time to demand restitution and resolution. We soar and fly by putting our feet down.

The piano rings persistent bells again on top of a fleeting kundiman melody. The singer raises their fist to the sky. The landscape suddenly shifts as the piano plays an otherworldly ballad, converging with the singer as if they were one and the same after all. A cadence lands on a D major, but it is merely deceptive in nature. Leaving the singer alone, the piano descends down to C-sharp as they intensely and knowingly glance back at us. There’s more to the story.

If you haven’t visited “Liham: A Digital Song Cycle” yet, I invite you to do so now: https://www.lihamproject.com.

See you in the next essay!

Sincerely yours,

Juro Kim Feliz