Entering the worlds of Liham

Juro Kim Feliz

(part 1 of 5)

[If you haven’t seen “Liham: A Digital Song Cycle” yet, I highly encourage you to go there right now: https://www.lihamproject.com]

Dear Reader,

I stared at a bunch of words on my screen on a July summer evening.

A tanaga — Tagalog quatrain verse — ushered a provocative mise-en-scène, preceding an English sonnet that lays bare the heart, soul, and spirit of a defiant people. The katipunero* suddenly flashed in mind, a brooding brown-skinned revolutionary biding their time until it’s ready to pounce. It both gripped and puzzled me. I expected a love letter. Instead, I read a manifesto.

Mezzo-soprano Renee Fajardo emailed me about creating a new song cycle a month prior. Fresh from the “Opera in the 21st Century” program at Banff Centre, she conceived Liham as a love letter to the Filipino creative spirit and an opportunity to mould stories around Filipino Canadian identities. Michel van der Aa’s interactive song cycle The Book of Sand inspired her vision of producing an online multimedia production at the outset — quite understandable with the impossibility of live performance during the global pandemic. And now, she wanted to commission me for this new musical project. A high-profile writer already declined to write the libretto. Knowing Revan Badingham III as a long-time collaborator back in Montreal, I tagged them instead to write poetry for this project.

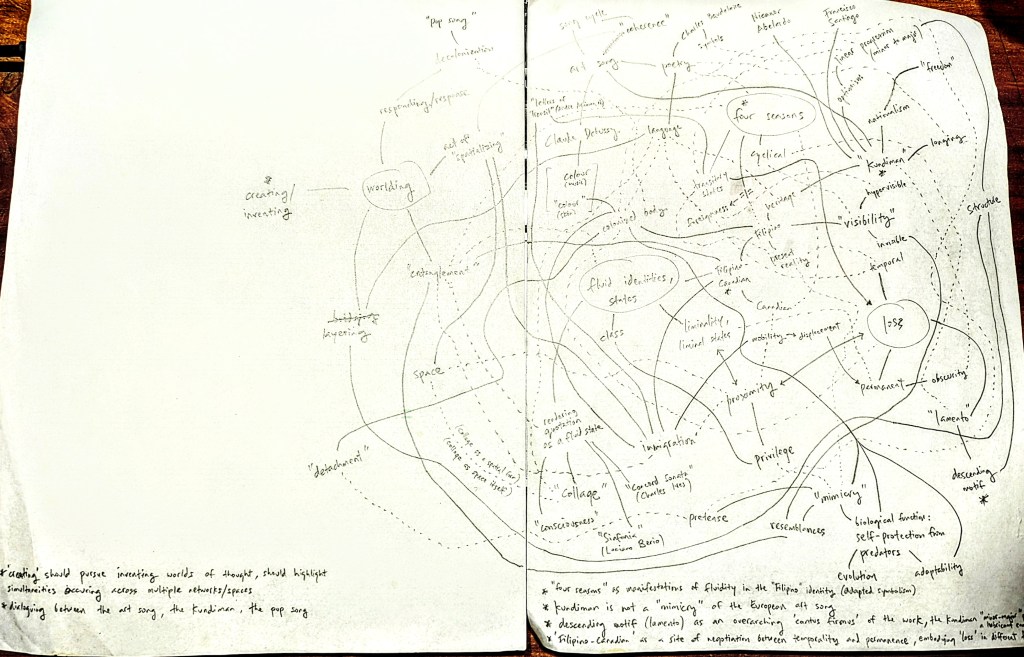

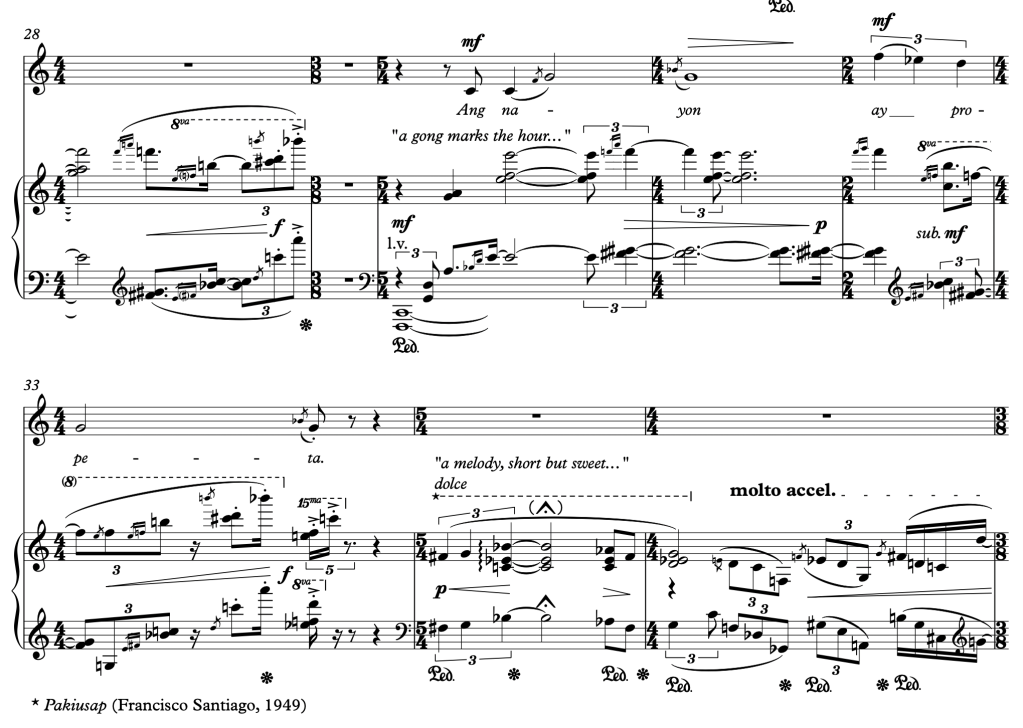

With my experimental musical inclinations, conjuring post-romanticism sounded both alluring and passé. I’ve never composed a song cycle nor any straight-up classical piece I consider part of my œuvre before. Do I know how to write one? Do I really want to sound classical? Claude Debussy’s Cinq Poèmes de Charles Baudelaire (1889) filled my ears to stir those waters. Compared to his other song cycles, Richard Wagner’s influence flirted with seminal impressionisms in Cinq Poèmes. I also took a nostalgic turn to the kundiman art songs of Nicanor Abelardo and Francisco Santiago, intensifying a gaze into my past life as a piano accompanist. It seemed inevitable to look into kundiman as if fate has tied us Philippine-born artists, past and present, into contending with colonial baggage.

However, I wanted Charles Ives and Luciano Berio to tell me more.

Concord Sonata (Ives, 1920, rev. 1974) and Sinfonia (Berio, 1969) have long fascinated me as a young composer, even as my aesthetics and artistic productions have gradually shifted into more socially-relevant inquiries. Ives conjured interjecting sound worlds — including Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, American marching band music, and ragtime — to paint the town of Concord, Massachusetts with the worlds of American transcendentalist philosophers. Berio’s third movement gushed out a torrential river of musical works that he ushered into a channel that is Gustav Mahler’s third movement of Symphony No. 2. In the documentary Voyage to Cythera (directed by Frank Scheffer, 1999), Berio summarized his approach: “Books, they talk to each other. Musics of different ages and different cultures too — they talk to each other.”

My former mentor Jonas Baes wrote a priori (2008) as articulated temporal disorder, taking off from the disappearance of experiential time in Walter Benjamin’s notion of modernity. In assuming an antithetical “Other,” Baes mashed sound worlds including Beethoven piano sonatas and Burmese sandaya piano in a piece that refuses logics of continuity. With its premiere also came the shits and giggles from Baes’ banter as I remember it: what if a commissioned Filipino composer writes Beethoven-esque music instead of a Western audience’s “Othered” expectations simply out of spite? Could we, historically underrepresented voices, dare do things and shatter the status quo out of spite?

I know colleagues who might dismiss intertextuality simply as a postmodernist (read: outdated) project, but I always respond with knowledge that colonial baggage will always ensure an intertextual, decolonial response. In decolonizing ourselves, we need to start somewhere. Reinventing lost histories and epistemologies can only go so far, although I’m always welcome to be wrong. I’m simply wary that treating erased cultures and histories as a set of tabula rasa of sorts will lead to further myth-making — the origin of nationalisms that legitimize and validate nation-states and their artificial consolidations of power.

Musical quotation is no stranger to me.

My first attempts came with the tune All The Things You Are (Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, 1939) for Bagatelle (Feliz, 2013) as an artistic response to Baes’ third of Five Bagatelles (2010). O forse, l’ho già perduta poco a poco… (Feliz, 2018) came next in line, conjuring Maurice Ravel’s Jeux d’Eau (1901) as a means to superimpose Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities (1972) over memories of my deceased piano teacher. Wesley Shen commissioned Kinaligta-án (Feliz, 2021), a harpsichord piece where I didn’t hesitate in quoting Abelardo’s Nasaan Ka Irog? (1923) as a feeble, fleeting centrepiece that renders everything else as mere canvas.

Creating my antithetical “Other” to excavate positionalities gave me an opportunity to challenge my own practice as a composer. Never mind the arrogant, sometimes imperialist undertones in seeking groundbreaking experiments and innovations. Sites of knowledge and artistic production — mostly saturated within institutions among the Global North’s abundant resources — can betray subtle imperialist tendencies. Even Liham doesn’t escape such clutches, but I digress. A new classical song cycle would serve as my playground for experimentation with musical collage and relevant intertextual panderings to Filipino Canadian worlds. All this while effecting a careful, inviting contemporary musical aesthetic.

Therefore, embracing a post-classical aesthetic secures a coherent system for Liham. That even includes conjuring a pop ballad sound in some parts. The kundiman repertoire is largely invisible in Western classical music histories — musical collages out of kundiman quotations could carry both strong potential and high risks. The kundiman’s visibility is long overdue, but adapting tonal material doesn’t warrant making them hypervisible against a jarring landscape that contrasts and negates them. This scenario renders their presences either comical, satirical, or questionable at best, undermining the delicate nature of the commission’s themes as a result. I needed to use a sonic palette that smoothens rough edges to make it work.

And so the wheels have turned…

…bringing me to read the words I now tossed, juggled, and smothered in my mind like shaved ice in halo-halo. Badingham’s first poetry draft spoke of revolution, retaliation, defiance — all romantic gestures precluding the forthcoming poetry of the rest of the art songs. The complexity of stories surrounding Filipino histories of struggle, revolution, and migrancy barely emerge from the water’s surface in the whiteness of North America. I have to jump on board. Debussy’s swirling fantasies over Baudelaire’s suggestive, sensual texts can wait.

Ives wrote his Essays Before a Sonata (1920) as a philosophical, passionate apology to the baffling dissonant interlocutions of the Concord Sonata. I always like seeing writings as a window to the music, akin to seeing B-rolls and BTS (behind-the-scenes) documentaries of well-loved movies. In this series of five essays, I will elucidate each art song per essay in an attempt to articulate reflections and thought processes that came along in completing Liham. Unlike Ives, I do not plan to write extensively with the same rigour, but I hope that this is a start to unpacking the work. This first instalment introduces overarching ideas around Liham as a song cycle.

Aren’t bass lines like invisible labourers?

They keep structures sound intact and grounded. They create coherence and nuance in harmonic landscapes. And yet bass lines are shrouded with perceptual invisibility until you notice either their absence or quirky attitudes. The head-bopping “oomph” of particular musical styles suffers without their grounding nature – sometimes to the annoyance of subwoofer-hating general public. In Listen to This (2011), Alex Ross devotes a chapter to spell out a short musical history through the “basso lamento” that emerged from the downward contours of lamenting expressions among many music cultures. This invented descending four-note bass line persisted throughout centuries, embedding itself in the 16th century chacona, the passacaglia/pasacalle (where Filipinos loaned the word “pasakalye” to mean an introduction to something), and — curiously enough — in the walking blues.

The basso lamento’s circular nature suggests a non-linear, open-ended temporality, one Ross described as “a liberation of the body…the swirl of a repeating bass line allows a [crowd] to forget, for a little while, the linear routines of daily life” (p. 54, brackets my paraphrasing). For a rigid cantus firmus that binds all voices into orbit, the lamento unexpectedly transforms into a means for escape and emancipation.

I structure Liham to articulate a lamento motif.

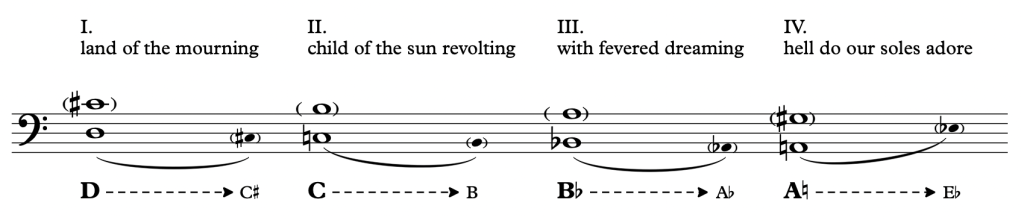

All four art songs adapt a tonal centre to spell a basso lamento in this sequence: | D – C – B-flat – A |. For chromatic contouring, I add a cadential destination at the end of each art song to act as a resolution toward the next song. The last song is an exception, its cadential note going upward to allow smoother movement back to the beginning. In doing so, I imply two things: (1) Liham can potentially behave cyclically in an endless loop, and (2) Liham underhandedly sings a lament underneath a celebration of heritage and identity.

What do they suggest? Firstly, I find it poetic to shape a song cycle in such a circular fashion. Jose Maceda conceived the Southeast Asian drone as infinity with an inner life rather than a tonal centre (1986). Whether melodic or rhythmic in nature, the ambiguity and persistent energies that patterns of loops, cycles, and repetitions create are desired musical expressions. We see this abstracted infinity among the gangsa in the Cordilleras, the kulintang in Mindanao, or even in casual kubing (jaw harp) or olimong (flute) playing for leisure. The gending and klenengan — vocal and instrumental repertories in Javanese gamelan — use forms that operate under looping colotomic structures. The gong ageng (largest gong) is notable in sparsely demarcating cycles, sometimes marking extremely long time passages underneath elaborate melodic spirals and swirls. But rather than Ross’ stipulation of looping bass lines to escape linear time, the drone stands as the de facto experience of time. Time is cyclical, if not infinite.

Secondly, there is a warranted melancholia in an emancipation that struggles to escape gravitational forces. The yesteryears of Filipino resistance against Spanish, American, and Japanese occupations now play out in an endless struggle against government corruption, systemic inequality, and neoliberal, capitalist machinations — sometimes even instilled by the Global North to keep wealth and resources within their reach. China’s brazen disregard of international law in South China Sea maritime disputes adds a new take on neo-colonial exercise of power. Some Filipinos still ask, “Are we truly free?” on every Independence Day. When will that cadential E-flat of the last song no longer preclude an inescapable loop back to the beginning?

But in replaying loops, we also destabilize order.

In explaining Judith Butler’s writings, Sara Salih argues that gaining a capacious understanding of something requires conjuring instabilities through repeated recitations (2004). Aoileann ní Mhurchú builds on this to explore the ambiguities of citizenship under continuous global migrations (2014). How do we displace understandings we assume to be clear-cut? Liham appeals to abstraction as the voice and piano obfuscate and displace clear-cut relationships. Instead of imposing a cold, objective finality on a thing, we engage in its fluidity, transience, and possibilities.

Remember Maceda’s observation on ambiguity as desirable in Southeast Asian musics? Gamelan tunings render an abstracted “pseudo-octave” rather than an exact 2:1 ratio. Philippine bamboo flute tunings similarly demonstrate abstraction on top of a command of theoretical knowledge in flute making. Kulintangan and gamelan players practice an abstraction of vertical time, not requiring strict synchronized playing as a group. Many attitudes — from indigenous musics and rituals to use of language and humour — operate on ambiguities and contextual frames, requiring a social game that secures interrelations within a society that values a shared sense of interconnectedness. To demand directness is rude, even indicative of an unwillingness to participate in this shared social game.

Forms emerge as displaced, fuzzy abstracts, waiting to be interpreted and used for greater, higher-level ways of meaning making. But we go further. While displacement is the condition and articulation of ambiguity, it is also the hallmark of mobility. Our ancestors are village folks and seafarers who can move at will, whether at land or sea. Translated into diasporic movement, displacement now unfolds in the present. People migrate and uproot themselves towards imagined futures. The condition of displacement now moves toward the condition of liminality and speculation. Liham taps into this potential to articulate the fluidity of identities, forms, and expressions as reflected in its subject matter: the peoples, communities, histories, socio-political realities, and new futures. These entities are never frozen in place. We need constant displacement to destabilize them and, consequently, see them fully legible.

Jason Josephson-Storm calls this metamodernist thinking a “social process ontology” (2021), where we see things as evolving, open-ended processes instead of frozen, well-defined essences under closed systems. I see the need for this when people start replaying the old record player yet again: “What is a Filipino?” (The corollary also comes out: What is ‘not’ Filipino?). This precludes the nationalisms that the majority of the Philippine population subscribes into — with all exclusions at play! As someone now living in Canada, does my Filipino identity cease to exist? Did I stop being Filipino all of a sudden? I see a need to break away from the fixation on “what a thing is,” as per Josephson-Storm. Liham subverts this premise entirely as it delves instead into both the realities of the homeland and the diasporas, tapping on a frame of inclusion and endless possibilities instead of an oppressive exclusion.

However, we need to see the multiplicities of space in order to activate worlds.

Going back to the music, I always look up to Doreen Massey (2005) when musical space comes into conversation. I fully believe that treating physical space as the sole medium of “spatial music” is misleading and outright lacking. Likewise for Massey, it’s a mistake to conceive space itself as a mere static, frozen container where you “put things into.” Instead, it materializes instantaneously in its entirety upon a conception of a thing. A thing embodies (read: not occupy) space, and its embodied space renders a thing visible and readable. Multiple things start existing, and space creates a working network of multiplicities that unfold all simultaneously. While colonizers and sites of power think they write history, the colonized and repressed create their own histories too. (That also goes to say that this inherent multiplicity and simultaneity is the entire problem of historiography: whose histories and their corresponding geographies count as “history?”).

It even goes to say now that all music is spatial in nature with all its abstract, physical, anatomical, and visceral geographies of meaning that unfold and interrelate organically — not only during its sounding but even during its very conception. Counterpoint is spatial architecture in all ways it can possibly exist. Once we spatialize music, we start engaging with the act of “worlding.” We manifest an ecosystem, a universe of orbiting entities, an open-ended system that brings forth visibility that happens to be auditory in nature. Music is not just acoustical phenomena per se — it constitutes interior and exterior universes that come to life and mobilize into sounds across physical space. Igor Stravinsky, you who once said that music carries no meaning; I declare you entirely wrong.

Realizing this, Liham conjures greater musical counterpoints beyond pitches and consonances, one of which entails parallel worlds where both voice and piano run ambiguous relations to enact a desired fluidity.

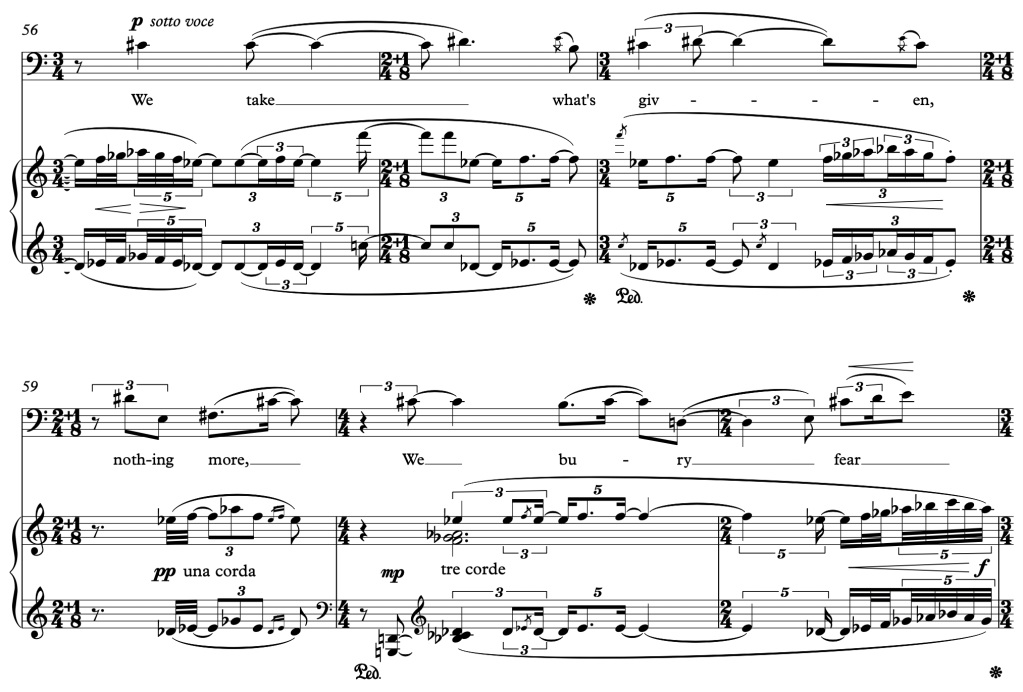

I implement this spatialization of Liham musically in two ways.

Firstly, the rhythmic impulses and treatment of time generally differ between the voice and piano. Vocal melodies are grounded in easily perceived beats, while the piano intentionally avoids sounding out regular pulsations in most parts. This creates tension between the rigid convenience of musical time in the voice and a fluid elusiveness in the piano — a theatricality that becomes painstakingly evident when performed live. Upon first hearing, a student of mine pointed out this resulting ambiguity to me: “They both sound out of alignment and yet they are obviously aligned.” The gamelan and kulintang ensembles behave naturally like that, so why not a song cycle?

The issue of simultaneity between the voice and piano becomes evident. It’s easy to conceive a shared musical beat in some parts. They have to make it work in other difficult parts. Each entity becomes an active agent, working as an ensemble to arrive together at a destination. The irony here is that keeping time fluid means keeping tabs of rigid counting, based on the practice of sounding out Western notation. An older colleague once told me that counting is a colonial concept. It may be so, but I consider it a tool nonetheless to initiate a different reframing. Maceda similarly composed his sound murals by way of notating polyrhythms that create dense clouds in massive numbers: 8 in 3 ½, 11 in 4, 5 in 2 ½, etc. (I literally looked at the score of Pagsamba [1968] as I wrote this). The goal is not to execute them down to the exact millisecond but to abstract them and activate an agency to perform them with others. At the end of the day, the collective simultaneity reigns supreme over singular performatives.

(Some side notes to the notion of counting as colonial: As a heavily colonized people, we have developed musical practices and forms that do rely on counting. That includes the kundiman, rondalla, and others rooted in Western forms. Are they still “colonial” musical forms if they have undergone their own indigenizations, leading them to sound how they are now? Additionally, while rigid counting may signify remnants of colonial thinking, the concept of convergence — running and arriving together at a destination — is definitely not colonial.)

Most importantly, both vocal and piano sound worlds embody independent trajectories. The vocal world roots itself a major seventh above/minor second below an art song’s designated tonal centre that the piano passages emulate. The first art song begins with the piano building its world on a D tonal centre, while the vocal melody first takes off from C-sharp. Other art songs follow this system. The “basso lamento” figure shown above demonstrates this structure, notated in parenthesis above the bass line. This detachment opens up the possibility of polytonality — superimposing two musical environments over each other at the same time — something I explored (albeit not fully fleshed out, I admit) in the third art song.

Vocal melodies generally sound very tonal, as if the singer simply sings cutouts of pre-existing songs. Contrastingly, the piano soundscapes bring out unapologetic dissonances, quirky angular turns, and shifting tectonic plates. The piano behaves like a soloist that the singer has to sing alongside with. These polarities provide me with the freedom of building musical collages with the piano, creating a new spatiality with the juxtaposition of my sonic impulses, kundiman melodies, and even pop-sounding tunes. The collage-making casts a non-diegetic element over the singer’s world as the singer remains unaffected with these outrageous outbursts of musical activity — akin to actors on a film’s interior world being oblivious and detached to the music score that accompanies their narrative’s unfolding.

That being said, is collage-making a mere exercise of scoring the vocal world? Not at all. In fact, I find it an opportunity for the piano to liberate itself from the confines of a collaborative role. The presence of an interior world, with all its simultaneous multiplicities and interrelations coming out of this collage-making, makes the piano a living character in its own right. (I will explore more details on specific kundiman selections and their conjured interrelations in the following essays). The collage becomes Maceda’s drone, articulating an infinity of spatial possibilities that possess an inner life of persistent pulsations. In Liham, we see not one singer being ushered by a pianist but two actual narrators speaking at the same time. The stratified simultaneities in Javanese gamelan exemplify such a frame.

Liham is written with a mezzo-soprano and a high baritone in mind. In contrast to the fixed nature of the piano’s instrumentation, the art songs can be sung by either voices. This intersection holds promise to its intended fluidity, as the gendering involved in vocal designations can be understated at times in vocal works. This is a problem I see with the kundiman repertoire and its romantic professions of love, in which many of the lyrics presume a specific gender as the speaker expressing love to a beloved — unmistakably seen at times as a pretext to the harana (a serenading tradition where a man serenades a woman in courtship). This unfolds even if singers of all genders do perform the kundiman in practice. Thus, Liham mirrors the kundiman’s capacity to subvert such gendering by allowing flexibility in vocal designations while also distancing itself from the patriarchal contexts of the repertoire’s lyrical content.

Finally, the interrelations between poetry and other texts create another contrapuntal layer.

More details came into light as Badingham progressed further in writing the libretto of Liham within the following months. With four art songs come different classical poetry forms for each of them: a Shakespearean sonnet, a villanelle, a rondeau redoublé, and a Petrarchan sonnet. (Further reflections on these forms will come in the following essays). The art song titles toy around the first four lines of the Philippine National Anthem, once translated in English by Camilo Osias and A. L. Lane during the American occupation. One could say that this English translation is a colonial remnant, now subjected to blatant deconstruction and deformation in the song cycle.

land of the mourning is the first song, named from the line “land of the morning.” child of the sun revolting is next in line, coming from “child of the sun returning.” with fevered dreaming comes third, taking its name from “with fervor burning.” hell do our soles adore sits at the end of the cycle, derived from “Thee do our souls adore.” Word play is extremely common in humour in the Philippines, but it also acts as political subversion. The titles are distortions, akin to lost futures now warped by colonial histories and ongoing narratives of oppression and struggle both in the homeland and the diaspora. I will delve into reflections on these narratives and their musical framing in the following essays. For now, I find that humour is simply rage dressed up funny.

Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss (ed. André Aciman, 1999) ultimately inform not only this song cycle but the digital project as a whole. This compilation of four essays by American immigrant writers creates a model for me to frame each song as written letters. Even with the defiant, revolutionary overtones of the libretto and resulting music, these angry and emotional-sounding letters call to look back into who we are, where we came from, what became of us, and what we should aspire for. All done in an act of love. Each art song in this digital iteration of Liham comes with attached stories of Filipino Canadians who Fajardo and I interviewed in Vancouver and Toronto. In the following essays, I will attempt to trace connections between these community stories featured in Liham and the Letters of Transit compilation.

Thanks for following me all the way here, reader. I hope that you will continue joining me in this journey. If you haven’t visited “Liham: A Digital Song Cycle” yet, I invite you to do so now: https://www.lihamproject.com.

Until the next essay!

Sincerely yours,

Juro Kim Feliz